CASE STUDY HOUSE #22: Julius Schulman sells the California dream as an ideal of a sleek, stylish,

efficient, glamorous, utopian, future-present living.

|

Slideshow: "Birth of Cool" at Addison Gallery

“Birth of The Cool: California Art, Design and Culture at Midcentury” Addison Gallery, Phillips Academy, 180 Main St, Andover | Through April 13

“Stollerized” Addison Gallery | Through March 23

|

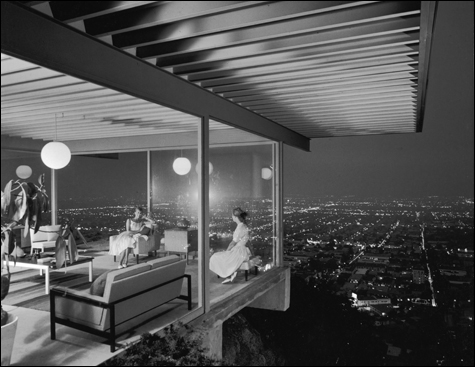

In the photo it is night, and two women in cocktail dresses sit — perhaps chatting while jazz plays in the background — in a spare modern living room. We can see in from the patio because the walls are glass, making inside and outside one. The horizontal slab of the roof seems to hover in the warm California air. A lounge chair sits at our feet — which means a swimming pool must be behind us. The house is perched high in the Hollywood Hills, and we gaze down across the Los Angeles valley, a sprawling grid of twinkling streets that seems an extension of the sophisticated geometry of the house.

Designed by LA architect Pierre Koenig, the house, Case Study House #22 (1959-’60), was one of 36 prototypes commissioned by the LA magazine Arts & Architecture between 1945 and 1966. Publisher John Entenza hoped the designs would be models promoting dashing, affordable modernist architecture. And the key is the photo. Julius Schulman sells the dream in his 1960 shot, an ideal of sleek, stylish, efficient, glamorous, utopian, future-present living.

This dream glows from the heart of “Birth of the Cool: California Art, Design and Culture at Midcentury” at Andover’s Addison Gallery. The minimal modern style fell out of favor in the 1970s and ’80s as its legacy of glass-and-steel box skyscrapers and brutal hunk-of-steel public sculptures came to seem cold, austere, and alienating. But the show arrives surfing the crest of the mid-century modern revival. Organized by the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, California, it is a terrific, thrilling exhibit, likely one of the best of the year, and part of its charm is its refreshingly non–New York focus.

Its title implies that the painting, furniture, decorative and graphic arts, film, and jazz here are united by geography. The focus is LA, and actually only part of LA — no Edward Kienholz, Watts Towers, assemblage, or Ferus Gallery. The real unifying factor is American “cool,” the now ubiquitous term coined by African-American jazz musicians that entered the mainstream as a description of stylish, seductive, unflappable, modern, hipster, manly aplomb. It is the cool of smart suits and cocktails and bachelor pads with just the right laid-back jazz spinning on the record player, and, of course, ladies. It is the cool of Playboy and James Bond, both of whom arrived in 1953, and John F. Kennedy, who joined the Senate that year.

The source of that title is a series of laid-back 78s that were recorded by Miles Davis with his nonet in New York in 1949 and ’50 and retrospectively collected as the 1957 album Birth of the Cool. They were touchstones for what became known as West Coast cool jazz. Gerry Mulligan, who contributed arrangements and original compositions as well as playing sax on the recordings, helped transplant the style to LA when he moved there in 1950 and formed a quartet with trumpeter Chet Baker before returning to New York four years later. But “Birth of the Cool” goes beyond the music itself to the image of the music as transmitted by LA photographer William Claxton’s portraits of cool guys and their gleaming instruments. As in Schulman’s iconic architecture photos here, it’s about style as transmitted by mass production.

Claxton wasn’t focused solely on the cool school — he seems to have shot everyone who passed through town: Davis, Mulligan, Bill Evans, Max Roach, Art Pepper, Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington. But his photos often have a sense of reserve, of hanging back. He nails the idea of the LA scene in shots of a 1960 Sunday jam session at Terry Gibbs’s house, North Hollywood. The guys play, casually gathered around a grand piano in an otherwise bare, wall-to-wall carpeted tract house living room as the California sun glows through the sliding glass doors that, of course, lead to a backyard pool where they’ve just been swimming.

After Hollywood, architecture and design were — and remain — the defining achievements of the mid-century LA scene. Artists tapped materials and techniques from the region’s aerospace industry, which grew out of World War II and blossomed during the Cold War. The signature house plans were minimal, open pavilions of floating geometric planes of steel and glass. The designers mixed Frank Lloyd Wright, Bauhaus, and Russian Constructivism to create a look that announced that a thrilling rocket-powered future had arrived. Part of that look’s appeal today is that it still offers that space-age allure, only now with a cozy patina of nostalgia.