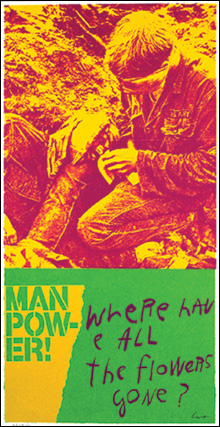

ACTIVIST ART: Kent’s Manflowers and News

of the Week (both 1969).

|

Sister Corita Kent was something of a celebrity. Newsweek put her on the cover as “The Nun: Going Modern” in 1967. She drew up a rainbow-striped “Love” stamp for the US Postal Service in 1985. She’s best known locally for designing the rainbow stripes painted across the giant National Grid gas tank off Route 93 in Boston in 1971. But she was never quite part of the fine art world, and since her death in 1986, she’s all but disappeared from art history.

So you might not know that Kent was one of the

best artists to emerge in the ’60s. Her giddy, neon pop art screenprints featured jitterbugging commercial slogans and long poetic quotations that vividly advertised her Catholic faith, called for civil rights and social justice, and opposed the Vietnam War. Which got her in trouble with the conservative Catholic hierarchy in LA, where she taught art for 20 years at Immaculate Heart College before leaving the order and settling in Boston in 1968.

As far as the art world was concerned, she had several strikes against her — a woman, religious, politically active and, dare I say it, popular. It didn’t help that she ended her career making schmaltzy greeting-card-style hearts, flowers, and rainbows.

These days Kent is having a tiny comeback. Julie Ault’s gorgeous book, Come Alive! The Spirited Art of Sister

Corita (Four Corners), was published last year. Some 40 Kent works were included in Mass MoCA’s 2007 show “The Believers.” And now Breslin Fine Arts in East Greenwich is presenting “We Can Cre-ate Life Without War,” featuring 45 Kent screenprints from the collection of Kent pal Rev. Bill Comeau.

The big American art movements of the 1960s — Minimalism and Pop Art — were cool, stripped down, and focused on formal matters. But Kent’s work was packed with meaning and often ecstatic. She anchored the spiritual in advertising slogans and street signs, which she turned into magic words. Wonder Bread became the bread of the Mass, which is believed to transform into the sacred body of Christ. The bounty of post-World War II America was the bounty of the Lord — rich, electric, fun, and juicy.

Kent’s work gets its high voltage from her masterful sense of typography, design, and color. In the early ’60s, her work was nearly all hand-written quotations plus brushy overlapping swatches of color. Around 1964 she brought in type, which by ’66 she was stretching and warping. In Help the Big Bird (1966), giddy texts — “Help the Big Bird/fall in love/Somebody up there likes us” — are twisted, chopped up, and spun upside-down.

NO NUKES: The 1985 piece Come Up

|

Great political artists need great political events, and as the ’60s went on, Kent rose to the occasion. As the news got darker — Vietnam War, assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. — her colors grew hotter and her content became darker, more mournful. She reached her peak with searing images made right after she left the convent.

Love Your Brother (1969) is a memorial to King’s 1968 murder. She writes “The King is Dead/Love Your Brother” across stacked news photos in glowing green and violet showing King in the back of a police car after being arrested in Birmingham and King hugging his wife after winning Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Such designs seem simple, but with well-chosen colors and a few words, Kent channeled the devastating loss and yet inspired with a call to carry on King’s work.

Around 1971, her work mellowed. DayGlo colors were out; rainbows and earth tones were in. But she continued to make political work. People assumed she hid the profile of Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh in the Boston gas tank stripes. (Kent maintained that people were imagining things — but didn’t mind that that’s what they saw.) She produced anti-nuke broadsides and critiques of our government’s actions in El Salvador, but her imagery became saccharine. Her anti-nuke piece Come Up (1985) is a doodle of flowers with the handwritten words “So far the crocuses have always come up” floating in the sky.

Ault chalks her departure from the convent to exhaustion from ideological battles with church honchos, a packed schedule of teaching and lecturing, and trying political times. After that fiery burst of work immediately afterward in 1969, Kent seems to have burned out and craved calm.

“Corita Kent: We Can Create Life Without War” |

Breslin Fine Arts, 187 Main St, East Greenwich | Through

May 15