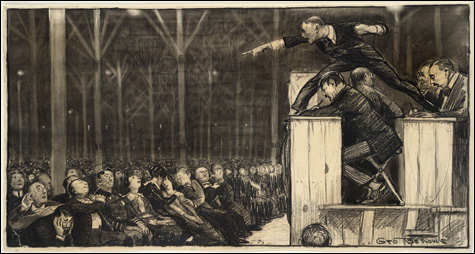

FIBONACCI CURVE: "Preaching," by George Bellows, March 1915. |

| "The Powerful Hand of George Bellows" through June 1 at the Portland Museum of Art, 7 Congress Sq, Portland | gallery talk with Carla Di Scala | 2 pm May 3 | 207.775.6148 |

The work of George Bellows has a peculiarly American brashness about it. The show of his drawings, prints, and a few paintings at the Portland Museum of Art reflects the culture of his time and demonstrates his formidable artistic skills. Bellows was active in the first decades of the 20th century; the confidence of the new American age comes through loud and clear.Bellows was born in true middle America, in Columbus, Ohio, in 1882. A successful athlete at Ohio State, he left without graduating to go to New York to paint. He studied with Robert Henri at the New York School of Art and became part of what was dubbed the “Ash Can School” of artists associated with Henri.

They were intent on using the whole of experience as the subjects of their painting. At the end of the 19th century the American art audience had expected classical or exalted themes in art and were surprised to see scenes of alleyways and tenements. The earliest drawing in the show, "Dogs, Early Morning," is, in fact, a picture of an ash can in a New York alley surrounded by hungry dogs. Bellows had a sure, clear hand, and his work and its then-unconventional subject matter gained plenty of attention. His early death at 42 of complications from a burst appendix prevented much of what he might have achieved, but he still accomplished a great deal.

His paintings are full of muscular energy, and there are several here. His reputation, though, was largely built on his drawings and illustrations. This show establishes easily that he was a master draftsman, right from the beginning. He chronicled events and personalities, illustrated books and magazine articles, drew satirical caricatures, and created imaginary renderings of real, horrible events.

The early 20th century in America was a time of invention and engineering optimism, with Edison electrifying the country and Ford giving it cars. Bellows experimented with various technical compositional schemes using formulas based on the Golden Section or geometric combinations of rectangles and triangles. In "A Knock Down," a drawing from 1917-21 chronicling the famous heavyweight title match in 1910 between Jack Johnson and Jim “Great White Hope” Jeffries, Johnson's right arm angles downward, pointing at the crumpled form of Jeffries as the referee counts between them. Johnson’s arm and the shapes of the other figures create triangles bounded by the edges of the paper. The position is a little unnatural, but it makes a dynamic composition with Johnson in the clearly, and historically, if not literally, correct superior position.

Those were also the days of the "sawdust trail" religious revival meetings that drew thousands, and Bellows made several works chronicling its most famous practitioner of the day, Billy Sunday. Bellows had a low opinion of Sunday, calling him “death to imagination, to spirituality, to art.” In the 1915 drawing "Preaching," Sunday and his crew dominate the right side of the picture while the rapt audience fills a cavernous room on the left. In his passion Sunday has leapt to the top of the desks where his henchmen are tallying accounts and is screaming and pointing into the audience, exhorting them no doubt toward salvation and generous contributions. The composition is based on a Fibonacci curve generated from a Golden Rectangle. The drawing is excellent and the satire is truly deadly.

This period in American art doesn’t get the attention it deserves. Bellows and his friends were working in an intellectual framework that had even then been superseded by the modernist developments in Europe. For them, the subject of the work of art was still its primary focus. Modernist art, as it developed from the Impressionists and Cézanne through to Matisse and Picasso and on to abstraction, showed that the work of art itself was the center of the relationship between the artist and the viewer, and that the subject, if there was one, was secondary.

But the fact that Bellows’s direction in art was supplanted to a great degree by modernism doesn’t mean that it wasn’t valuable. This show gives us a welcome chance to go back and look again.

Ken Greenleaf can be reached at ken.greenleaf@gmail.com.