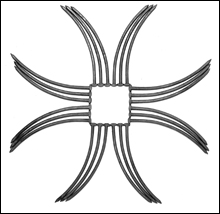

"PLUME" 2001-2, from Ton series, welded 12-inch spikes. As installed at the artist's workspace.

|

The Portland Museum of Art’s new exhibition immediately confronts you with the transformative power of John Bisbee’s sculpture. Two grids of monumental glyphs formed from flattened, twisted hand-forged nails climb up the walls of the museum’s Great Hall, communicating in an uninterpretable but strangely familiar language. You peer into the main gallery space to see an entirely different museum, spacious and with a warm, ambient glow: the mysterious dropstones of Bisbee’s work selectively illuminated with bright, focused light. Rather than beginning on a prescribed curatorial path, you can’t help but scan the sightlines reaching out to the distant corners of the gallery, each individual piece part of a well-manicured landscape. The actual space of the museum, at least in recent memory, has never looked so good.

This spatial sensitivity translates to Bisbee’s sculptures. Each one is. Autonomous but adaptable to its surroundings, they are evidence of their unseen creator’s devotion to the ever-present moment, even when installing a piece from decades past.

Nails! That’s what we’re dealing with here, but you’ve got to get past that. Bisbee’s knack for constructing large-scale works composed of nails, brads, and spikes would surely have run out of steam in his twenty-odd years on the job if there weren’t something else at work here.

You might even be able to find that something in the exhibition, since it’s a retrospective. We are granted a rare opportunity to see a chronology of Bisbee’s work that would more likely be encountered individually. By examining nascent nail works from the late ’80s and recent synergetic experiments, we see Bisbee’s own transformation as human, artist, and teacher.

“Strong Box” from 1988 reflects his initial interest with the nail motif. Four windows allow the viewer to peer into a heavy, handled case. Buried inside, bristling, is a bed of upturned nails looking something like rusted moss. There is an intention inside the sculpture, and the metaphor is clear that it is not yet ready to see the light of day. The title of the piece, “Cocoon,” evokes a similar trepidation.

HAMMERED: Hand-forged nails, from

"Untitled," 2008, from Ton series.

|

Quickly, in the relative scale of a life lived, Bisbee’s work moves from caged impulses to the playful, experimental, and didactic. The early ’90s bring about “Spool,” composed of a thin layer of nails, welded lengthwise to create a hollow cylinder. The weight of the nails is alchemically rendered insubstantial, each one appearing to float by the good grace of its neighbors.

“Square” takes on the traditionally hung art object. Four layers of brads, thinly arranged in the style of “Spool,” are transposed to form a proxy canvas. Dimensionality is in constant flux. Two dimensions become four, then back to an illusive two, reminiscent of ice crystals on a window pane or bacillic bacteria under a microscope.

“Plume” and “Dendrite” face off in vine-like patterns up the twenty-plus feet of opposing walls in the main gallery. “Plume” is a wild, organic growth with anthropomorphized tendrils of metal creeping out of the white wall, screaming for your attention. “Dendrite” is seven years the other’s senior and reveals a calm curiosity concerning the human mind. Nails similar in origin to those in “Plume” are now flattened and arranged in synaptic repose, cleanly squared off with tight boundaries and halved by the corpus callosum of the white wall.

Bisbee’s path to individuation over this unique timeline seems best exemplified by “Helio” from 2006. Hundreds of twelve-inch spikes are carefully arranged in a perfectly placed honeycomb crown. The artist remains faithful to his medium, but continues to explore the ways in which his artistic activity and intentions can expand their boundaries. In this case, gravity is the only adhesive and a Zen-like clarity of purpose and patience are the only things needed to get the job done.

John Bisbee’s successful practice is evident not only in the impressive sculptures on display, but also in the way he and his work engage the museum and the city. Docents answer questions from curious visitors, both parties more animated than usual. Hoots and hollers broke what could have been stuffy silence at the exhibition’s opening and the PMA’s accompanying book is a beautiful crossroads of design, photography, academic text, and creative prose. This energy suits the museum well, allowing it to be a cornerstone of the contemporary. Undoubtedly, John Bisbee will help push that envelope as far as he can.

On the Web

John Brisbee: www.portlandmuseum.com

Ian Paige can be reached at

ianpaige@gmail.com

.