NAOMI “There was something of a toll that women or girls paid when they got next to Black Flag.” |

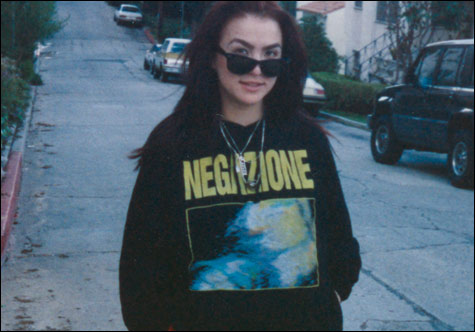

Naomi Petersen was not famous. Neither was she semi-famous, almost famous, post-famous, or notorious. Nonentity, indeed, seems to have been closer to the elements of her nature than celebrity. Success (conventionally measured) was of little interest to her; at times of stress she was a blackout drunk; and the love of her life was the no-hope clangor of the LA punk-rock underground. She died alone in a hotel room, in 2003, at the age of 38, and it would be years before some of her friends even knew she was gone.

And now there is a book about her: Enter Naomi: SST, L.A. and All That . . . (Redoubt Press). Why? Because one of those friends was Joe Carducci, prose master and author of Rock & the Pop Narcotic. Carducci got to know Petersen at the start of the ’80s, when he was working for SST Records and she was a meek, damaged, but adventurous teenager, parlaying her skill with a camera and her intuitive relationship with the SST roster into an unofficial gig as the label’s house photographer. Black Flag, Minutemen, Meat Puppets, Hüsker Dü, Saccharine Trust, Saint Vitus: the jutting, image-allergic strangeness of these bands entered the prism of her lens and came out somehow . . . viable, without being in the least palliated or diminished. Carducci watched Petersen grow as a photographer and as a woman, admired and pitied her for the shit she had to take in an uncompromisingly male, low-rent environment (“There was something of a toll that women or girls paid when they got next to Black Flag” ), and then — as the fires of punk rock shrank to the brooding embers of pre-Nirvana “alternative music” — lost touch. Hearing of her death two years after the fact, in 2005, he was horrified; in his subsequent attempt to rescue something from the oblivion that had overtaken their friendship can be found the germ of this remarkable book.

I’ll call Enter Naomi a sentimental memoir — which is not to suggest the least level of mushiness or dishonesty but simply to note that its dominant key is not, as in Rock & The Pop Narcotic, theoretical or historical but emotional. There is theory in it, certainly, and plenty of historical scratch ’n’ sniff (no one will ever write a better book on Black Flag), but Carducci’s considerable literary triumph is the manner in which all of this is, as it were, incarnated in the person and the progress of his faltering heroine. In Petersen’s bold, against-the-odds attachment to the SST bands and their ethos, her gut-level affinity for the music, the fragility and perishability of her art, and the fact that none of this remotely equipped her for the demands of a “real,” non-punk-rock life, Carducci finds his emblem: Naomi slipped away, and how much slipped away with her. “I think of Naomi as a transition figure,” he writes. “To an extent all women are transition figures which is why we open doors for them, but the arts they now inhabit in greater numbers are no longer the drop-out wilderness they were when young Naomi pulled that door open for herself. . . . All that waste of money and time in liberal arts programs, film schools, etc. I say dynamite them all, for art’s sake. All of this middle class safety, so well-camouflaged by tattoos, piercings, porn vamping, suicide kitsch . . .”

The above extract is a fair example of Carducci’s thorny professorial style, and if you’re troubled at all by that loud ptoing! sound as the geezerish wad of his contempt hits the old spittoon, then you may return at this point to your iPod and your books about Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Carducci is crankily unapologetic in his conviction that the American musical rebellion of the early ’80s, particularly as manifested in the South Bay area of Los Angeles, was freakdom’s last stand. “Our closing frontier,” he writes in Enter Naomi, “was the sixties cultural revolution as it died out in the seventies and early eighties. In retrospect the Black Flag/SST story looks like a cultural analogue to the Manson-Weathermen-S.L.A.-Black Panther-Nixon White House-People’s Temple endgame — art just had more life in it than crime or politics or religion.”

Maybe all elegies are manifestos in a sense, and all manifestos elegies. At the heart of it all, of course, are Black Flag — a band, Carducci writes, “evolved to withstand failure on any scale.” Chaotic, imprisoned head music allied to huge discipline: the indeflectibility of Greg Ginn, Flag’s founder/guitar genius and SST boss, was as impressive as it was merciless, and it left plenty of people behind. Among other witnesses, Carducci is kind enough to cite, as fringe testimony, my own portion of the SST literature: an unauthorized biography of Henry Rollins that I wrote back in the Grunge Age. He needn’t have, but as a brief turner over of stones in that area I can vouch for his evocation of the SST world as a sort of Darwinian bohemia, where minds and bodies exposed themselves to constant hazard in pursuit of some quite unnamable satisfaction. These people lived under desks, with strips of floor carpeting for makeshift curtains, eating crackers and dogfood. And when they went out on the road, everybody wanted to beat them up! I exaggerate only slightly. They were, Carducci writes, “the best people money couldn’t buy,” in an age when involvement with good music “cost you something.”