FANCY FREE The youthful adventure of Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein still resonates in this

1944 work. |

It's almost enough to make you nostalgic for World War II. Jerome Robbins's 1944 Fancy Free, in which three sailors enjoy a hot summer night ashore, is a ballet about young men feeling their oats, enlivened by camaraderie. Then-25-year-olds Robbins and Leonard Bernstein were doing the same thing in creating this work, and their delight in their shared adventure still resonates in the choreography.

>> PHOTOS: Boston Ballet's Fancy Free <<

I was once fortunate enough to hear New York City Ballet star Damian Woetzel talk through the narrative choices behind each gesture in Fancy Free's opening variation. Staged by NYCB dancer Jean-Pierre Frohlich for Boston Ballet (in a production at the Opera House through May 20) most of the subtleties were in place. Strolling through the city streets in neck-craning unison, clicking their heels, the trio are like proto-Jets to whom Robbins has taught the hornpipe. As the sailors stick chewing gum into their mouths, Fancy Free may be the only ballet in history that makes high art out of littering.

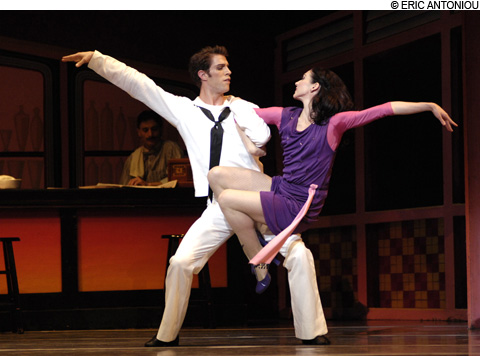

Each sailor exposes his particular nature. In last Friday's cast, Isaac Akiba was an adorable showoff, leaping from the diner counter in side splits; Paul Craig was the moonstruck lover, and a technically reliable partner; and Robert Kretz wrapped himself in a suggestive rhumba. As the passer-by with the purse, Erica Cornejo overdid Robbins's flouncy sass, but balanced Ashley Ellis's newspaper-reading siren nicely as the women made an unexpected alliance, wise to male hyperbole. Bernstein's score is a rumpus of big-band jazz and boogie-woogie cozying up to those spacious Aaron Copland chords Bernstein never really abandoned. Conductor Jonathan McPhee rinsed it bright.

Peter Martins's 1988 Barber Violin Concerto, getting its Boston Ballet premiere, originally paired two New York City Ballet stars, Adam Lüders and Merrill Ashley (in pointe shoes), with two modern dancers, David Parsons and Kate Johnson (dancing barefoot). Johnson and Parsons were Paul Taylor alumni. Ergo, Martins grafted ersatz Taylor signatures to a Balanchine vocabulary. The result is a sour parable of the buttoned and the unbuttoned.

In a kind of sexual vampirism, the ballet woman (immaculate Kathleen Breen Combes) spasms her arms into the broken line of the prowling modern-dance guy (Sabi Varga) and literally lets down her hair. The modern-dance woman (a feisty Misa Kuranaga) skitters around like a nagging mosquito and uses poet-shirted Artjom Maksakov as a jungle gym. Violinist Lydia Hong's muscular playing stoked the edginess under Barber's lush melodies.

In a refreshed production of Harald Lander's Études, this ode to academic technique has its origins in the daily syllabus of the Royal Danish Ballet's Bournonville class. From the spotlit legs in brisk barre exercises to the rondes de jambes done in canon, the ballerinas' legs looked like elegant trim stitched beneath the shelves of their black or white tutus. Silhouetted against a blue backdrop like Victorian cut-paper valentines, they seem to be every little ballerina's dream.

Friday's performance, however, suffered some glitches. Lorna Feijoo, though lovely in the sections that quoted La Sylphide, was off her game. Pavel Gurevich lacked control in a work that is singularly unforgiving of sloppiness. But as Feijoo's matched consorts, Jeffrey Cirio was the confidently spinning center of a troupe of six fouette-ing ballerinas and Isaac Akiba sailed like Sleeping Beauty's Bluebird. Études has its corny aspects, but it goes beyond pastiche to be a dance about ballet's aspirations.