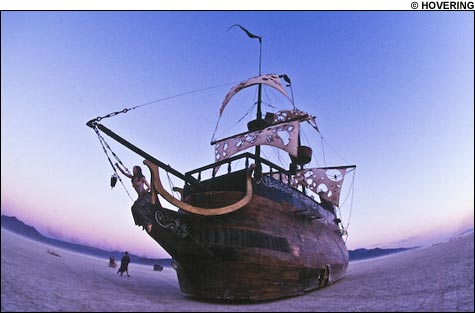

ZACHARY RUKSTELA helped design a scaled-down 16th-century galleon (above), plunked it on top of a school bus, and set sail for the 2002 Burning Man festival. |

A post-civilized life

Most modern conveniences are manufactured to be replaced. Steampunk art can be interpreted as a rebellion against soulless design, homogeny, and Wal-mart-ization. And the act of “Steampunking” the things that surround us has, for some, become a thrilling revolt against the evils of mass-production and the subsequent commercialization and commodification of every last inch of our lives. “It seems to me that we’ve developed into a disposable society,” says KSW’s Orlando. “Items are manufactured to be disposable and cheap. They’re not made uniquely or to last — they’re made to be affordable. Care and creativity is taken out of the process.”

In addition to everything else it has the potential to do, the Steampunk scene is about DIY resourcefulness, and encourages people not to consume, but to re-use, to create, and to celebrate the advantages of the one-off. “There really is a saturation of new gadgets that are really crappy, that won’t be an heirloom or anything you’ll ever save,” says Phil Torrone, senior editor of MAKE magazine. “I think there’s a need for people to build something that will mean more to them.”

For some, this translates to a deeper study of their patterns of consumption and use, and there are a number of individuals who have chosen to further unpack Steampunk until it’s suspended inside of their personal philosophy. For every link to Steampunk-themed ephemera, you’ll find endless debates about its boundaries and its meaning. So is it an aesthetic technological boom? A nostalgia-drenched affectation that bleeds into the neo-Weimar gothic-cabaret explosion? Or is it more — a cultural movement?

Magpie Killjoy, the pseudonym of the Portland-based publisher and founding editor of SteamPunk magazine, believes Steampunk is all of those things. Although, for the “anachronistic anarchist,” it’s the necessary alternative to the quid pro quo of contemporary society. “I think Steampunk can save the world,” he says. “I’m not saying it will, but I’m saying it could. Our civilization has reached its endgame, most likely, destroyed by industrialization and neo-colonialism.” Killjoy lived in squats across the US and Europe for several years and discovered that, to his pleasure, Steampunk was “like punk, but with better manners.” He chooses to live a thoroughly post-civilized lifestyle — as if our planet has already self-destructed. “We graywater, we compost, we garden, we dumpster and recycle all in our tiny yard in the middle of the city,” he says. “Steampunk appeals to us. It encourages us to remember that technology is neither savior nor foe.”

Killjoy launched SteamPunk magazine in the fall of 2006, initially as a means of self-publishing one of his short stories. Four issues (not including an extra mini-issue, “The Steampunk Guide to the Apocalypse”) have been published thus far, averaging 80 pages in length. The magazine offers a rich range of literary excerpts and stories by new writers, intellectual essays on the “Varieties of Steampunk Experience,” and feature pieces on everything from “How To Turn Copper into Brass” to an introduction to DIY millinery. They’ve run interviews with up-and-coming Steampunk musicians, tech-artists, and writers like Steampunk power-couple Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, who edited a new anthology called Steampunk (Tachyon) that will be published this June. With the assistance of a group of writers, editors, and artists, Killjoy runs the magazine on a completely volunteer basis, and anyone can download it for free under a Creative Commons license.