The gravitational center of Steampunk is a longing for a past that never was. It was a time when a computer could indeed run on steam, when dapper gentlemen with clean shirt cuffs and pocket watches could be mad scientists by night, and when an object’s uniqueness and aesthetics were just as important as its functioning guts. If you think of it as an exuberant amalgam of the modern with the 19th century, you begin to get the idea, but you’re barely dipping your toe into the ocean, because Steampunk isn’t merely a not-so-secret fringe culture any longer. It has developed a set of values that, for some, go deeper than a hobbyist’s nostalgia for an age they weren’t around to experience. The Steampunk ideology is in no way uniform — like the culture itself, it can be taken apart and put back together to suit its makers — but it seems to be ingrained in a combination of radical politics, an anti-corporate, do-it-completely-yourself ethic, and an acceptance that we are already living in the dystopian future we’ve been warned about.

Von Slatt compares his love for Steampunk to the popularity of stories that began with Victorian fantasy-fiction writers and continue to pop up as a constant meme in everything from Disney’s adaptation of Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, to the late ’60s television show The Wild Wild West, to role-playing games like Forgotten Futures, to Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic book. “It’s the same reason why people love mash-ups: people love it when you mix their favorite things together,” he says. “When the characters from Crossing Jordan show up on Las Vegas. When they have chocolate in their peanut butter. Steampunk is the same thing.”

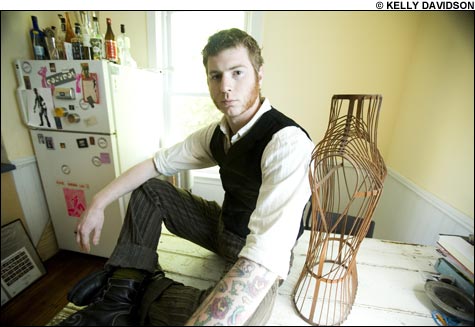

MANOR BORN: Jamaica Plain resident David Dowling has created the Meandering Manor, a mobile Steampunk platform. |

The fiction we will become

The current Steampunk Workshop, virtual and literal, started with von Slatt’s Victorian RV — the 1989 Thomas Saf-T-Liner school bus he converted into a camper. Posting how-tos on a precursor to his site, he accidentally unearthed Steampunk’s online community. He came into it not realizing there was an entire subculture to define both his DIY habits and the visual aesthetics he’d long appreciated. Once he launched the Workshop, visitors identified themselves much in the same way. “Again and again, people post, ‘I had no idea there was a name for what I am,’ ” he says. “A lot of it seems to have come from the same place simultaneously, a mysterious force bringing us together.”

It wasn’t long after von Slatt’s mods were showcased across the Internet that he became known as a leader in the Steampunk backyard-industrialist movement, a role that makes him uncomfortable. Rather, he describes himself as a connector, a sort of Steampunk dad who possesses a talent for putting movers-and-shakers in touch with each other so that big things can start to happen. When I meet him, it’s a week before the May 3 and 4 Maker Faire in San Mateo, California, a creative DIY festival organized by MAKE magazine. It’s at Maker that von Slatt will finally get to meet, in person, a number of the contemporaries with whom he’s corresponded. Maker hosted von Slatt and several other Steampunk celebrities in the Contraptor’s Lounge, a show-and-tell discussion salon.