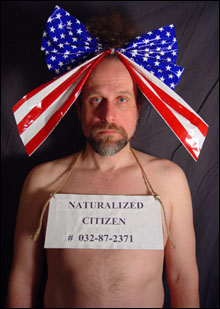

Milan Kohout

|

For performance artist Milan Kohout, freedom of speech has prevailed. His legal woes — stemming from a political protest in the Financial District — were the subject of a recent Phoenix editorial. State prosecutors this past Friday asked Boston Municipal Court Judge Annette Forde to dismiss a widely criticized criminal charge against Kohout, according to Kohout’s pro bono attorney, Jeffrey J. Pyle.

In November, Kohout mourned the tragic human toll of the subprime-mortgage crisis by staging a protest in front of Bank of America’s Boston headquarters, setting down hangman’s nooses on the sidewalk next to a placard reading “Nooses on Sale.” Boston Police, woefully unversed in the First Amendment, stopped the protest and charged Kohout with being an “unlicensed transient vendor.” The police were serious about pursuing the bizarre and trumped-up charge against the artist, who came to Boston as a political refugee after being expelled from his native Czechoslovakia in 1986 for his pro-democracy activism. But the district attorney, either in an exercise of good judgment or in response to the sudden publicity, thought the better of it.

“I am gratified that the Commonwealth has dropped this absurd charge, which was an attempt to punish me for exercising my right to freedom of speech,” says Kohout. “I grew up in a totalitarian system which misused the law to prosecute dissidents for their critical expressions. For the government to use bogus charges to punish artists for their expression is a step toward that kind of system.”

Commentators disagree over the value of Kohout’s protest. The Herald called his message “absurd,” while the Phoenix hailed Kohout’s likening of Bank of America’s corporate officers to hangmen as “uncomfortably brilliant.” And passers-by couldn’t have been blamed for thinking Kohout’s statement was a racial one, in light of the noose’s long history as a symbol of anti-black hatred.

But the First Amendment does not pass judgment on the effectiveness or clarity of a protest, and it is clear that Kohout’s activity was just that — a constitutionally protected symbolic protest, not a literal vending of nooses. That the police officers who responded to complaints about Kohout were unable, or simply unwilling, to make such a distinction is troubling news worthy of an internal investigation.

One solution would be to train Boston police officers in constitutional rights along with their lessons in firearms and interrogations. Knowledge of — and obedience to — the First Amendment should be considered a necessary skill for any American cop.