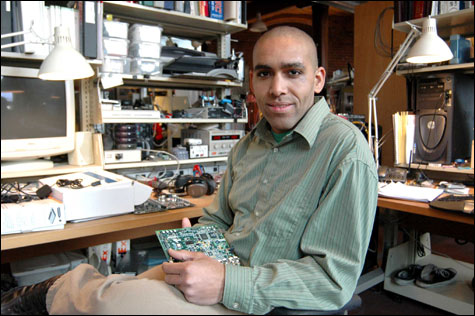

BRAIN POWER: The Ocean State needs a lot more people like Bradford, who calls his staying here after graduation from Brown “almost a freak accident.” |

Rhode Island is lucky to have Kipp Bradford.

The affable 33-year-old Pennsylvania native, a 1995 biomedical engineering graduate of Brown University, works as the vice president of engineering at Design Lab, a Providence-based product invention and design firm that exemplifies the kind of “innovation economy” sought by the Rhode Island Economic Development Corporation (EDC).

Bradford thinks the local job landscape has improved since the time when he graduated from Brown 12 years ago. He serves on the board of AS220 and socializes with the Providence Geeks, a small, yet strategically important group of tech-savvy thinkers and digital entrepreneurs. Still, looking back to his graduation, “There wasn’t an awareness in my mind of what I would do in Rhode Island,” Bradford recalls. “It’s almost a freak accident that I found this job.” And as it stands, he’s not aware of any other engineering students from his class who remained in Rhode Island, although one recently returned to take a teaching job at Brown.

People like Bradford — creative, interesting, intellectually curious individuals — aren’t an endangered species in Rhode Island. Yet the unmistakable presence of such individuals obscures a larger problem: how the state, which has struggled to recapture the economic glory of the Indus¬trial Revolution, lacks enough good jobs, leading smart young people to often pick up stakes and move elsewhere.

There are many exceptions. Take the case of Paul Tencher, a 26-year-old West Warwick native, now the chief of staff for Lieutenant Governor Elizabeth Roberts, who won the job after successfully managing her 2006 campaign. Landing this kind of high-level role at a relatively tender age shows how Rhode Island’s small scale and pleasant quality of life offer some big opportunities — a theme, not coincidentally, of the EDC’s marketing efforts.

Still, for every such example, there are scores of other college-educated young people — the kind that this aging state needs to retain, to spur economic growth and to serve as taxpayers — who flock to other states in search of better opportunities.

This realization dawned anew two days into 2007, thanks to a front-page story in the Providence Journal — headlined “RI exodus: Losing the young, ambitious.” Mark Arsenault’s piece, which attracted House Speaker William J. Murphy’s notice during the opening legislative session, described how this “brain drain” has driven declines in the state population for the last three years.

Saul Kaplan, executive director of the Rhode Island Economic Development Corporation, prefers to see the glass as half-full, pointing to such assets as Rhode Island’s rich array of colleges and universities, and “the advantage that we have in having the brains in the first place.” To hear Kaplan tell it, one of the biggest hurdles to progress is psychological — aggressively pursuing a new “innovation economy,” instead of trying to hang onto the bygone industrial age — and he says the state is on its way.

As salesman No. 1, Governor Donald L. Carcieri is also upbeat. “I think the picture’s a lot better than some of the anecdotal evidence,” he told me during an appearance last week on WPRI/WNAC-TV’s Newsmakers, pointing to recent study that included Rhode Island in the top-10 on available jobs. “I’m very optimistic that we’re moving that ball,” Carcieri said, adding that the state simply can’t absorb all the graduates of local colleges and universities.

Still, it’s got to be a little worrisome for the governor when as stalwart a supporter as ProJo op-ed columnist Edward Achorn points to the brain drain and a litany of other concerns, as he did Tuesday, ultimately rebuking the governor’s cheery State of the State tone by writing, “Pardon me for saying it: The ship of state is not on a safe course.”

And one has to wonder, after all these decades, why the state isn’t farther along when it comes to economic development.

Who stays, who goes?

As a fairly recent University of Rhode Island graduate, 23-year-old Meghan O’Connor has a lot of friends who moved to New York or Boston for jobs after finishing school. Yet after interning at the RDW Group and Rhode Island Monthly, and then winning a job at the magazine during her senior year, she elected to stay in the state, and now works as the communications coordinator for the Economic Development Corporation.

“I feel you can get more done here in Rhode Island” than in a more populous place, says O’Connor. “Working at the EDC’s kind of exciting now,” she says, because, “hopefully, 10 years down the road, Rhode Island’s going to be that [economically innovative] spot.”

One has to wonder, though, if O’Connor would have stayed in the state were she not a native of Warwick and North Kingstown.

While there are certainly notable examples — like Rich Lupo, the proprietors of Al Forno, and Lightning Bolt drummer Brian Chippendale, to cite an eclectic trio — of people who stayed and made an impact after attending local colleges, the connection is often stronger for those who have familial ties to the state.

According to US Census data cited by the ProJo, Rhode Island gained small numbers of people from other states from 2001 to 2003, and then started losing population — a net of 2114 people in 2004, 11,618 in 2005, and 12,566 in 2006.

These decreases are all the more jarring because of how Providence’s national reputation has steadily improved over the last 20 years, and because of how Rhode Island has served as an affordable alternative for home-buyers fleeing Massachusetts and other states.

At any rate, the interpretation of this data set off a lively skirmish on the Journal’s op-ed page. RISD president Roger Mandle responded by citing how Rhode Island “actually out-performed New England in job growth in the ’00s for the first time in decades.” URI economist Leonard Lardaro, who was quoted in the initial story, fired back by citing how the state’s weak tech sector softened the blow of the dot.com meltdown, buttressing his argument that Rhode Island needs to reinvent itself — and fast.

Regardless of whether one sees the glass as half-full or half-empty, there’s not much dispute about the basic problem.

As put by Darrell West, who has seen student migration for more than 20 years from his perch at a political science professor at Brown, “I think the state is doing poorly retaining young people just because there aren’t enough well-paying jobs. The students who come out of the state’s universities and colleges generally have to look elsewhere, even if they want to stay in Rhode Island.”

On a smaller, but important level, the plentiful cheap mill space that helped to spark the collective art space Fort Thunder in the mid-’90s, raising Providence’s appeal to independent-minded artists, has vanished. And while the residential conversion of old industrial properties might raise municipal tax revenue in Providence, it exacerbates a squeeze on commercial space for artists and small businesses.

“It is very challenging for young people to find jobs or to find actual space to launch businesses,” says Laura Mullen, coordinator of the Sustainable Artist Space Initiative, a collaborative backed by the Rhode Island State Council for the Arts and other groups. While the Providence underground continues to attract people, “I do feel that we’ve lost many individuals and many, many businesses that have had to leave the state because of lack of opportunity and lack of available space.”

Maureen Moakley, chair of the political science department at the University of Rhode Island, says Governor Carcieri, a Republican, and Democratic legislative leaders seem to be seeking a broader vision of statewide economic development.

(In one controversial step touted as a “business-friendly” move, Carcieri and the legislature last year backed a $15 million tax cut for wealthy Rhode Islanders. Because of the state’s $350 million structural deficit, the governor has recently proposed cutting a similar amount of state-subsidized child-care for working families.)

Yet for too long, Moakley believes, there has been a lack of vision and an excess of parochialism on economic development: “We don’t want a port, we don’t want a casino, we don’t want LNG in our backyard, or an airport runway extension,” she says, paraphrasing opponents. “If you look at Boston, and if you look at New York, how can you expect to develop sophisticated economic structures in a global environment under those kinds of restrictions? If we want to remain a pretty backwater, those are the consequences.”

Okay, so now what?

Saul Kaplan, who took over the Economic Development Commission’s reins from Mich¬ael McMahon last year, acknowledges that Rhode Island “needs to be far more aggressive in taking advantage” of the existing brainpower in the state. “The issue isn’t that people are leaving,” he says. “The issue is that there aren’t enough opportunities for them to stay.”

The overriding goal, Kaplan says, is leveraging Rhode Island’s “incredible location” and “incredible knowledge power” to raise from 40 percent the quantity of high-wage jobs in the state, while simultaneously strengthening other parts of the economy. At the same time, he says, it’s critical to preserve Rhode Island’s distinctive sense of place.

Kaplan points to the creation a few years back of the Science and Technology Advisory Council (STAC), co-chaired by top educators at Brown and URI, which he credits with “a perfect track record of making specific recommendations to increase our innovation economy.”

Rhode Island, composed mostly of small businesses, has suffered from a lack of diversity in its economic infrastructure, so Kaplan, not surprisingly, cites the importance of growing some sectors, like information technology and digital media, while building on strengths in health-care, life sciences, marine and defense, and professional services.

Kaplan, who studied to be pharmacist at URI, says Rhode Island’s small size means that “it doesn’t take a lot to get to the tipping point where we can change the game.” As one example, he points to how the EDC’s Business Innovation Factory is moving forward with a plan to make Rhode Island the first state covered by wireless Internet access.

Under Carcieri, the state has also backed efforts to upgrade adult education — an important need — although seriously im¬proving statewide public education, particularly in poorer communities like Providence, very much remains a work in progress.

While the market has cooled, housing costs in Rhode Island doubled in a five-year period, making the state far less affordable than it had once been for home-buyers, particularly for young people.

There are rudimentary things that can be done to support the state’s economic development efforts.

URI economist Lardaro, for example, cited a need for tracking data on the number of people who graduate from Rhode Island institutions and who become employed here for their first job.

Blogger-activist Matthew Jerzyk (an occasional Phoenix contributor) stayed in Providence after graduating from Brown in 1999 because of the sense of connection that he felt as an activist. He thinks the state should foster stronger connections between students and opportunities in Rhode Island. “This can take many forms — internships, fellowships, partnerships,” he writes in an e-mail interview, “but the common thread is simple: building relationships and connections (and thus an investment) between a student and the state.”

For his part, Kaplan expresses optimism that, in “10 years, we’ll look back and we’ll have a very strong innovation economy.”

If it were so easy, though, the state would perhaps already be enjoying smoother sailing. As Lardaro has noted, the skill drain in Rhode Island “has the unfortunate consequence of making it even more difficult to amass a critical mass in high-tech.”

Different approaches have been tried — incentives, tax breaks, and small business grants — and yet the state remains in a familiar position. There’s also a certain measure of mystery in why companies locate where they do, and what proves most successful in creating jobs.

While Rhode Island has some considerable assets, they haven’t been enough to help recapture more than a fraction of the state’s bygone economic vitality.

For every young person who has ever come to this state and wished that they could stay, the “innovation economy” can’t happen soon enough. The problem is, for too many, it will be too late.