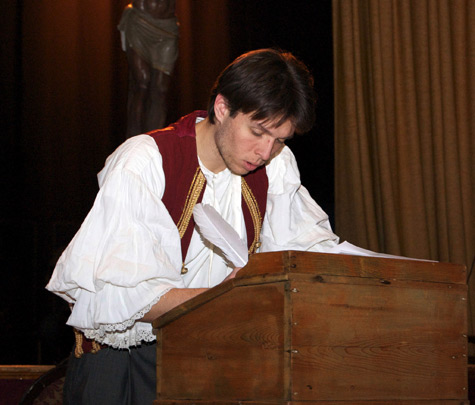

GENIUS AT WORK Bryan Kimmelman as Mozart. |

As a play, Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus has more than its share of theatrical muscle: Strong and compelling characters, an absorbing storyline, clever structure, and a pretty classy soundtrack. The playwright’s film adaptation couldn’t much improve on the stage potential. It’s heartening to see that going in the opposite direction budget-wise, from big screen to church auditorium, doesn’t have to lose anything essential. Elemental Theatre is putting it on at Providence’s Beneficent Congregational Church, and the production is exquisite.

Directed by Alexander Platt, we get everything we need and then some. Excellent actors, three of them Actors’ Equity. Live music — strings, keyboard, and four operatic vocalists. Thanks to production designer Sara Ossana, the set is minimal but opulent on occasion, such as a rococo purple velvet couch that extends for miles in Act Two, to convey the excess and opulence of the royal court in Vienna. The dark wood of the vaulted ceiling doesn’t hurt, either.

Amadeus is such an absorbing story because it’s about twin passions — the young Mozart’s for music and his older court rival Salieri’s for revenge. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was more than a prodigy, he was a genius, writing his first symphony at age 5. As a child, he was shown off by his father Leopold to the courts of Europe. Antonio Salieri was a Venetian composer in the employ of Emperor Joseph II, obtaining the prestigious rank of Kapellmeister in the late 1780s.

As imagined here, Salieri (Max Vogler) at age 16 made a pact with God: purity and devotion in exchange for success as a musician; the very next day a benefactor sent him to Vienna to study music. “Notes of music are either right or wrong,” he informs us, hardly prepared to appreciate the imaginative inspiration of a composer like Mozart (Bryan Kimmelman). Amadeus means “loved by God,” which Salieri takes literally and as a divine affront. Salieri’s first impression of Mozart is as an “obscene child,” cavorting sexually with his fiancée, Constanze (D’Arcy Dersham). Moments later Salieri hears “the voice of God,” beatific music being played by this upstart. He’s tormented that this vain young man can produce “casual notes which turn my most considered ones into lifeless scratches.”

Salieri is telling us this story partly as a confession, partly as a taunt. Three decades after Mozart’s death, Vienna is abuzz with the rumor that he is claiming, in deathbed delirium, to have murdered Mozart, poisoning him. Vogler’s Salieri makes us sympathetic in spite of ourselves, as he keeps bringing us back to the point of view of the engaging villain. By the end of Act One, Salieri has waged war on God — you’ve got to admire a guy who picks such ambitious fights. And you’ve got to feel a twinge of fellow-feeling for the source of such rage. “Let your sound enter me,” he implores heaven. “Need me!”

As Mozart, Kimmelman is properly boyish and enthusiastic, and by that has the easier role. But he certainly adds plenty of entertaining grace notes. His Mozart is a self-confident, precocious boy too kind-hearted for his own good. The closest he gets to anger is annoyance at the dullness of Salieri’s compositions: “Pom-pom-pom-pom. Tonic and dominant from here to resurrection! Not one interesting modulation all night!”

Vogler and Kimmelman remain Salieri and Mozart, but the four other actors play multiple roles. Dersham, Tanya Anderson, Kelly Seigh, and Philippe Bowgen sometimes cluster as a commenting chorus and sometimes play variations on pomposity as officials of the imperial court, although Anderson’s Emperor Joseph II is a simpleton rather than one of the pretentious.

Everyone here does their job so well, and though this drama is leavened with humor throughout, it grows quite moving by the end. A feverish, dying Mozart is haunted by the loss of his harsh father, whom the composer reimagines as a frightening presence concluding his opera Don Giovanni. Salieri assumes the guise to haunt his nemesis, but his rancor fades.

In the 1780s, Salieri was believed by Viennese cognoscenti to be one of those impeding Mozart’s success. Whether or not it was true, it was a good story — but as a tale it doesn’t hold a candelabra to Shaffer’s elaborate extrapolation here, a paean to musical genius and Olympian Schadenfreude.