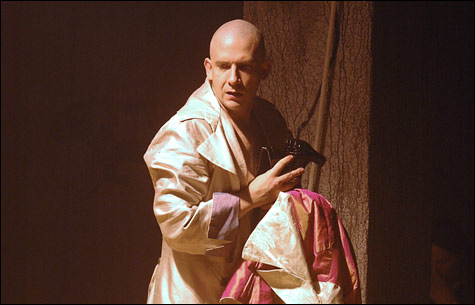

TITUS ANDRONICUS: The gore may be understated but the violence is not. |

Actors’ Shakespeare Project handles Shakespeare’s biggest bloodbath without turning on a single spigot. Into the rarely produced Titus Andronicus (at the Basement at the Garage Mall through April 22) the Bard stuffs horrors like clowns into a Volkswagen, hewn limbs, lopped-off hands, and torn-out tongues piled on top of the usual rape, murder, and mayhem popular in the Elizabethan theater in which the author came of age. But rock breaks plasma in director and set designer David R. Gammons’s staging of the lurid early tragedy for ASP. “I tell my sorrows to the stones,” says the title character, pleading for the lives of two of the 24 sons he loses before and during the course of the action. The play’s vivid imagery — critic Harold Bloom calls it “this poetic atrocity” — repeatedly alludes to stones, which, along with ropes that bind, become a motif in a dark, stylized, all-male production that is bloodless only in the literal sense.

In Bloom’s view, Titus Andronicus, which was first published in 1594, is “exploitative parody, with the inner purpose of destroying the ghost of Christopher Marlowe” in the young Bard. Set in fourth-century Rome, the play also riffs on the myth of Philomel, the closet dramas of Seneca, and the popular, revenge-laden works of Thomas Kyd, whose The Spanish Tragedy was among the London hits the arriviste Shakespeare doubtless hoped to emulate. Many scholars postulate that parts of the play, which is certainly among Shakespeare’s cruder efforts, were written not by him but by the lesser Elizabethan dramatist George Peele.

None of this renders the play any less fascinating, and ASP actually makes a valid case for it in an elemental, ritualistic, and very masculine staging surrounded on four sides by audience and what look like cave paintings. Although the gore is understated, the violent imagery is not: Titus calls Rome “a wilderness of tigers,” and if no one is torn apart here, humans are routinely trussed up like animals. Neither is the poignancy stinted, as gross evils and calculated revenges pile up like bodies on a battlefield. The play’s Job-like title character sets his own tragedy rolling in the first scene, when, returning from victory over the Goths, he orders one of their number religiously sacrificed despite the pleading of the prisoner’s mother, Goth queen Tamora. There ensues an orgy of serial violence among the families of Titus and Tamora climaxing in the old, half-mad Roman’s baking the Goth’s sons, who have raped and disfigured his only daughter, into a pie that he feeds to their mother. It is only at this grotesque climax that the ASP production starts to pluck the black comedy that has hung ripe on the vine almost since the beginning. It is perhaps a tribute to the production that I laughed just twice — once at a line that was ludicrous without being horrifying and once when, after Titus’s sudden murder of his daughter at the cannibal feast, the emperor Saturninus, having first leapt to his feet in surprise, calmly took another bite of pie.