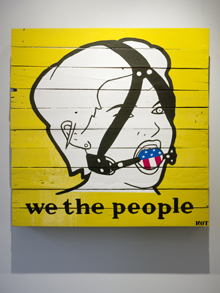

IN-YOUR-FACE West’s We the People. |

The art world and the Occupy movement have a somewhat awkward relationship. Many artists have sympathized with Occupy's call for greater economic equality and have participated in the protests and encampments, but the art world's long disinterest in work that directly engages with politics beyond ethnic, gender, or sexual identity has left "fine" artists flatfooted. The art that has stood out in the movement has been graphics — sleek professionally designed posters, hand-scrawled placards, and "bat signal" projections onto buildings.The exhibit "#Occupy" at Yellow Peril Gallery (60 Valley Street, #5, Providence, through April 15) sort of splits the difference between activist street graphics and fine art. And much like the movement, it comes across as well-intentioned, scrappy, at times brilliant and inspiring, and sometimes kind of ragged.

Melissa St. Laurent's straight documentary photos of Occupy encampments and marches in Providence and New York is the best work here. Veterans for Peace wave flags; a woman in New York holds a cardboard sign reading "We voted for change not spare change." A bandana hides the face of a statue of General Burnside atop horse in Burnside Park, where Occupy Providence camped out last fall. You can feel St. Laurent's support for the cause as well as the energy and soul of the activists.

Phil LeStein's inkjet prints rework found cartoons of couples by adding tongue-in-cheek — and somewhat predictable — words about how the Man sees the movement, such as when a guy looks up form his reading to tell his wife, "Honey, the paper keeps writing favorable articles about Occupy Providence!"

Tom West paints graphic images of a woman gagged with American flag above the text "We the people" and a hand giving the thumbs down with the text "Government + Wall St. = same thing." Joey Kilrain's digitally-printed, graffiti-style cartoon depicts the Statue of Liberty stripping for cash. West and Kilrain have the in-your-face, simplified style of street placards, an approach that works well and is often necessary to advertise messages on boisterous streets, but that can come across as hectoring and lacking nuance in the more quiet, contemplative atmosphere of galleries.

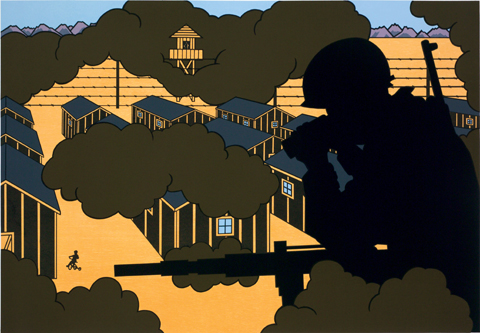

SAD ABSURDITY Shimomura’s American Guardian. |

At the other end of this political art spectrum is "Roger Shimomura: Lithographs," a quiet rumination on injustice in a new, small expansion of Rhode Island College's Bannister Gallery (600 Mount Pleasant Avenue, Providence, through April 6; Shimomura speaks on Thursday, March 29 at 4:30 pm at RIC's Alger Hall 110).

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered that West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry — at the time designated as "foreign enemy ancestry" — be forcibly relocated into internment camps to prevent them from doing harm to the United States. Nearly 120,000 people were moved, forced to abandon homes, shops, and farms, and imprisoned for the duration of the war.

"My first memory of life is celebrating my third birthday in camp," Shimomura writes at the bottom of his lithograph of a cake on a table in an empty room with a blue star banner on the wall and barbed wire visible out the window. Born in Seattle and now long based in Kansas, he spent two years of his boyhood interned with his family and 9000 other Japanese Americans at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in the desert of Hunt, Idaho.