SORRY, STEVE The A.R.T.’s tinkering has helped push this revered musical drama away from minstrelsy and toward myth — with new momentum. |

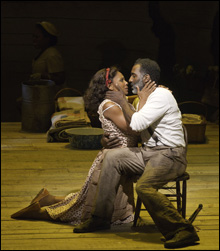

So shoot me, Porgy purists. To my mind, the retooling of The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess for American Repertory Theater (at the Loeb Drama Center through October 2), intended to make the iconic folk opera work as a Broadway show, is compelling enough to push past quibbles. And in Audra McDonald it boasts a Bess as pained as she wrestles her devils as she is languorous and melodious in her delivery of the music. When on opening night she and Norm Lewis entwined their voices around "Bess, You Is My Woman Now," toward the end of the first act (there are only two), I thought I'd died and gone to some auditory equivalent of the Promised Land those denizens of Catfish Row keep singing about.For those of you who do not follow such wars, a New York Times interview with the creative principals behind this streamlined Porgy and Bess (renamed The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess by mandate of the Gershwin estate) drew a scathing letter from musical-theater deity Stephen Sondheim, followed by a general outcry, with its implication that director Diane Paulus and her team of adaptors, Pulitzer-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and jazz composer Diedre L. Murray, were out to "fix" a masterpiece. Well, it ain't necessarily so.

When last I saw Porgy and Bess, in the famed 1976 Houston Grand Opera revival of the work by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin, it was aurally and visually ravishing but a bit turgid. And, of course, the line that the work treads between archetype and racial stereotype has always been squiggly. Here, both the tinkering by the linguistically gifted Parks and a strong abstract set by Riccardo Hernandez help push the piece toward myth and safely away from minstrelsy. But the production's real accomplishment is to bring to the Gershwins' and Heywards' musically rich drama a sense of momentum.

Though there is mention of a month having passed between the abandoned Bess's rescue by Porgy and the picnic that puts her back under the murderous Crown's sexual spell, the story seems here to play out in real time. And it has an exquisite arc, beginning as it does with Nikki Renée Daniels's Clara alone onstage singing an achingly lovely, vibrato-less rendition of "Summertime" to her baby and ending with Porgy's singular, mournful self-expulsion from Catfish Row. In the rollicking in-between, where the story unfolds against composer Gershwin's heart-stopping mix of operatic tradition and African and American jazz, gospel, Tin Pan Alley, and blues, there is the glory and tragedy of community.

I am not offended by Porgy's being bumped up to the late 1930s or by the crippled hero's trading in his goat cart for a cane and later a leg brace. (The only terrible idea had by the collaborators — to tack on a happier ending, as 19th-century bowdlerizers did to Shakespeare's tragedies — got nixed before the opening.) I did somewhat miss the exotic, impoverished warren of Catfish Row. But Hernandez's brutalist curve of crude boards is suitably abstract, and it performs an effective trick during the climactic hurricane. And Lewis's twisted if dignified Porgy, sorrowful as he comes to an understanding of what love requires him to do and near-orgasmic when he's done it, makes us feel not just the frustration of Porgy's disablement but the pain of his every step.