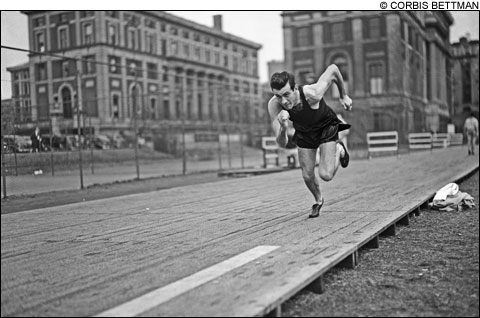

PROBLEM CHILD The same scrappy defiance that made him a teenage scourge also made Louis Zamperini a hero. |

When Laura Hillenbrand was doing research for her first book, Seabiscuit, she kept coming across references to another fast-moving morale booster of the Depression: Louis Zamperini. Louie (as Hillenbrand calls him) wasn't shrimpy or knock-kneed like the equine champion, but for a while he too seemed anything but a hot bet. As a teenager, he'd turned into the town troublemaker of Torrance, California, a twit without a future who could nonetheless run like heck to get out of a jam. Seabiscuit and Louie shared a capacity to come storming up from behind, a talent that served as a metaphor for hope during the dreary, depressed 1930s.

Hillenbrand spent seven years amassing a mind-boggling amount of historical detail to tell Louie's story in Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. Like Seabiscuit, this new book maintains tension even though its outcome was determined decades ago and is proclaimed in the title. Readers not drawn to war histories might all the same find themselves addicted to Unbroken, what with Hillenbrand's vivid style and flair for sneaking in suspenseful teasers. At one point, bored gunners shoot at whales and discover that bullets lose their speed just a couple of feet into the water. "One day, this would be very useful knowledge," writes Hillenbrand. Hmmm.

Already a Depression-era high-school track star by the time he entered the Army, former problem child Louie ran a 4:14 mile on the morning of the day his clunker B-24 crashed into the central Pacific. He'd been fixated on making the 1940 Olympic team; all the running he'd been doing had left him in his best shape ever. His adolescent scrappiness was of a piece with his optimism and ingenuity. As a kid, we're told, "Louie had regarded every limitation placed on him as a challenge to his wits, his resourcefulness, and his determination to rebel. . . . Now, as he was cast into extremity, despair and death became the focus of his defiance."

Louie was stranded with another sturdy soul, his pilot, Russell Allen Phillips (a/k/a Phil), and the two spent hours grilling each other about their pasts, bent on preserving their sanity in the middle of a blank sheet of sea and sky. At one point, they launched into "White Christmas," singing it "over the ocean, a holiday song in June, heard only by circling sharks."

That Louie and Phil survived at sea for 47 days is astonishing in itself. That he then endured more than two years as a POW in Japan — starving, freezing, getting beaten, being used as a slave, living on top of a cesspool — might make a non-religious person start to reconsider.

When Louie tried to settle back into life in California, his torment translated into nightmares, booze, an almost broken marriage. What changed his life was hearing Billy Graham speak: in a second, he saw his survival as preordained. He came to see God behind everything that had happened, and he decided to spend his life as a Christian speaker. It's a tidy fairy-tale ending. Maybe too tidy — he once told a friend he hadn't felt anger in 40 years.