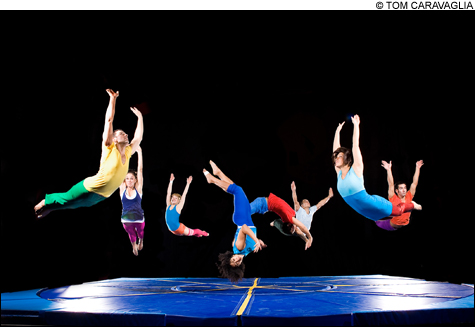

TRUST FALLING The STREB company in action. |

Midway through last Wednesday night's performance of "Raw" by the dance company STREB, Cassandre Joseph stood frozen atop a metal scaffolding extending nearly the full height of the Merrill Auditorium stage. She stared down as the MC, Zaire Baptiste, instructed the crowd of over a thousand people to create a thunderous racket, encouraging her to take the plunge. A young girl sitting in front of a friend and me plugged her ears. Like soccer teammates during a penalty shot, the seven other company dancers watched anxiously from the periphery. At last, Joseph leaned forward, extended her limbs like great wings, and plummeted face down, landing with a thud on a padded mat.

STREB (both a surname and backronym standing for Strength, Trust, Risk, Energy, and Body) is a self-styled "extreme action" dance company founded by Elizabeth Streb. Taking elements from the fields of acrobatics, yoga, modern dance, and the circus while fully belonging to none, the company offers a truly singular take on modern dance concepts. A former ballet student who moved toward modern and avant-garde dance in San Francisco in the early '70s, Streb started her company in 1975 with a simple belief: human beings can fly.

Merce Cunningham once wrote that "an art process is not necessarily a natural process; it is an invented one." For Streb, the exploration of the art of human flight begins with a natural one: falling.

"When I came to New York in 1974, I was asking questions about action," Streb said in a phone interview after the October 27 performance. "I wanted to know why dance as an art form at that time didn't change its base of support more often. It spent all of its time on the bottoms of its feet. It was a serious lack of questioning on what could be the body in motion on Earth."

To be sure, Streb's interest in getting feet off the ground wasn't purely aesthetic. "A great ballet dancer certainly is moved by passion of many sorts, but when I see ballet, I see — and I think the working classes of the world would agree — an enormous amount of privilege encased in a very arcane set of activities."

In 2003, she began S.L.A.M., (the Streb Laboratory for Action Movement) in a vacated warehouse in Brooklyn. It's less of a school than a sort of NASA for professionally trained dancers. In addition to touring performances like the one at Merrill, STREB keeps open office hours during the week, with the public invited to witness rehearsals, trials, and explorations. Today, her company of 8 "actioneers" includes former ballet dancers, gymnasts, actors, tumblers, and capoeiristas, as well as numerous technical and artistic production assistants. The live performance attests to a radical expansion of the limits and tone of modern dance.