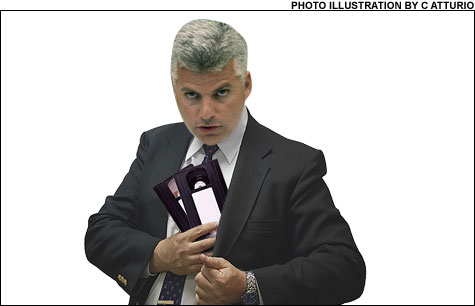

HIDE AND SEEK: Suffolk County DA Dan Conley is willing to go to court to keep a surveillance tape tied to a Revere cop’s murder out of the Lynn Daily Item’s hands. |

In terms of drama and scope, it’s not quite the Pentagon Papers. But an intriguing battle pitting government against the press is currently percolating on the North Shore and here in Boston.

The showdown — which involves the Daily Item of Lynn and Suffolk County District Attorney Dan Conley — has its origins in the fatal shooting, on September 29, 2007, of Revere Police Officer Daniel Talbot. (Disclosure: I worked at the Item for four months in 2003.) The murder of a cop always packs an extra emotional wallop, since the men and women of law enforcement risk their lives to keep the rest of us safe. And in Talbot’s case, some added details — including his age (30), his imminent nuptials, and reputation as a nice guy and good cop — made his death seem particularly tragic.

At the same time, ever since Talbot’s murder hit the papers and the airwaves, the circumstances surrounding it have been perplexingly murky. For one thing: why were Talbot, his fiancée, and several other police officers hanging out behind Revere High School at 1:30 am? For another: prosecutors have acknowledged that the group’s members were having “a couple beers.” How many is that, exactly?

And here’s a third lacuna. Conley originally said that Talbot was killed after his group had a “heated exchange” with 17-year-old Derek Lodie, who then called several friends to the scene. One of these, Robert Iacoviello, 20, allegedly shot Talbot in the head. (Iacoviello has been charged with Talbot’s murder; in addition to Lodie, James Heang and Gia Nagy, both 17, have also been charged as accessories.) Since then, however, prosecutors have acknowledged that Talbot initiated the exchange in question. What did he say, exactly? And what transpired between his initial comments and his murder?

The answers — some of them, at least — may exist on videotape that was shot that night by a camera mounted on the wall of Revere High School. But when the Item requested a copy of the video this past December, Conley’s office refused. And when the paper tried again later that month, explaining in greater detail why it felt its request was justified, Conley’s office again chose not to make the tape available.

Fast forward to earlier this month. On February 7, the Item filed suit in Suffolk Superior Court in yet another attempt to obtain the video. Right now, a hearing on the matter is scheduled for March 19; the goal, from the paper’s point of view, is to convince the court that the Massachusetts Public Record Law (MPRL) mandates the tape’s release.

“We as an organization believe that the taxpayers of the city of Revere deserve to know what happened that night,” Item editor Henry Collins tells the Phoenix. “There are a lot of questions leading up to the time surrounding Officer Talbot’s death. Maybe there are answers on the videotape; maybe there aren’t — but if there’s nothing on it, then we should be able to say that.

“This was a videotape made with a camera placed on a public building, videotaping a public field, and as it turns out a public officer was killed,” Collins adds. “We believe it’s a public record based on that.”

For its part, the DA’s office is arguing that tape is part of an ongoing investigation — and that its release could improperly harm the defendants. “Our take, frankly, is that the defendant simply couldn’t receive a fair trial if the videotape were broadcast,” says spokesman Jake Wark. (His assumption — which may be correct — is that the tape would make its way from the Item to local TV newscasts upon release.)

In theory, the investigatory exemption is a tough one to obtain: it’s limited, according to the text of the law, to materials whose disclosure would “probably so prejudice the possibility of effective law enforcement that such disclosure would not be in the public interest.” What’s more, Conley’s office has already made multiple arrests in the case, which could make it harder for the DA to argue that disclosure would be detrimental. “It won’t disclose a confidential source,” argues Peter Caruso Sr., the Item’s attorney. “It won’t impede the prosecution of a perpetrator. It just doesn’t fall into any of the categories for an investigative exemption.”

On the other hand, Massachusetts courts have tended to look skeptically on attempts by the press to obtain video evidence. The best-known example came in 1993, when the Supreme Judicial Court barred the release of videotape from a police line-up following the murder of Carol DiMaiti Stuart. Stuart was killed by her husband, Charles, who blamed a nonexistent black man for the crime and later committed suicide. The tape in question, which was sought by WBZ-TV, showed Stuart falsely identifying an innocent man as the perpetrator. But despite the fact that the ensuing grand-jury investigation was complete — and that much of the information of the tape had already been made public — the SJC unanimously ruled that, as a product of grand-jury deliberations, it couldn’t be released.