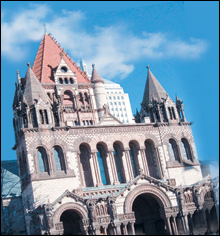

LANDMARK DECISION H.H. Richardson’s Trinity Church is among the endangered buildings whose fate rests on how seriously Governor Deval Patrick takes the threat. |

Much of the heart and soul of historic Boston — the gorgeous 1840 townhouses of Louisburg Square, the North End’s colonial-era churches, the tree-lined avenues and brownstones of the Back Bay — is in danger of sinking into the marshy ooze on which it was built over the centuries. It appears that Governor Deval Patrick doesn’t grasp the scope of the threat or the need for the state to treat it as the environmental danger that it is.

While his administration’s agencies are actively doing their part in the short term, working with the city to mitigate the most immediate problems, Patrick wants to bar the state government from long-term efforts to keep the city’s structures standing. In particular, he has filed a bill to excuse his Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) from regulating development on groundwater-dependant lands.

And Tom Menino, while admirably marshaling city agencies for the task over the past two years, seems more concerned with protecting his political control over development than in forging a long-term solution.

Often recognized as an issue for Back Bay homeowners, groundwater depletion poses a much wider danger. H. H. Richardson’s Trinity Church, which defines Copley Square, is at risk. So are majestic Brahmin homes on the water-facing side of Beacon Hill; quaint residences of the South End reclaimed in recent years from encroaching urban decay; tightly packed Chinatown homes and shops behind the Beach Street paifang gate; gentrified apartments above tiny eateries on cobblestoned North End streets; and Fort Point warehouses reborn as artists’ lofts.

If this is not an environmental issue that should be of concern to the state, nothing is. Groundwater is to Boston what levees are to New Orleans; at risk are the homes of thousands of residents, along with the very structures that make Boston the “Hub of the Universe,” a preferred destination of tourists, students, and workers.

Thousands of Boston’s buildings, built on fill that turned harbor and swamp into usable land, are in danger of collapse. They are supported on wood pilings that keep the structures above the water that still lurks beneath the surface. And, while it may seem counterintuitive, the wood now depends on that very water: when the groundwater levels drop, it exposes the pilings, which dry out, rot, crack, and eventually collapse.

Rainwater and melting snow should constantly replenish the groundwater. But for decades, we humans have prevented these natural sources of water from getting below ground: we’ve paved over the soil and pumped water away to prevent flooding or to allow for construction, and have let the groundwater leak into pipes and underground structures. And we keep on doing it.

The stakes are enormous, and we are already seeing the consequences. One Back Bay family had to climb out a window after their house shifted due to rotted pilings, says Jerome Smith, chief of staff to City Councilor Michael Ross. Others have had to evacuate houses deemed unsafe. Some have spent a quarter-million dollars or more to install new steel-and-concrete underpinning to keep their homes standing.

“We depend on the groundwater for our entire neighborhood,” says Jackie Yessian, chair of the Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay.

Other cities built on filled land, such as Milwaukee, St. Louis, and St. Paul, eventually solved the problem through “urban renewal” — tearing down the old neighborhoods and rebuilding. Boston did the same on a small scale in the 1980s, when a group of Chinatown homes was deemed too damaged by depleted groundwater to repair.

Eventually, that is exactly what will happen to Boston if the groundwater levels aren’t cared for with constant vigilance — and fast. Imagine the Back Bay rebuilt, without the rounded brick bays laid by Victorian-era craftsmen. Imagine the North End rebuilt without any trace of Paul Revere.

In other words, imagine Boston turning into just another city.

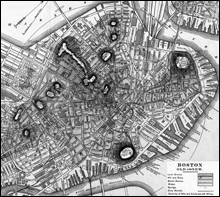

STAYING AFLOAT: Much of the city’s prized real estate sits on man-made land. If groundwater levels fall, a wealth of 19th-century architecture falls with it. |

Years of governmental neglect

For years, both city and state government abdicated their responsibility to monitor, regulate, and protect Boston’s groundwater levels. Finally, in the past 18 months or so, Menino and various local and state agencies — the BRA, the MBTA, the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the MWRA, and the state’s Office of Environmental and Energy Affairs — have stepped up to form a non-binding agreement to address the issue through a City-State Groundwater Working Group. In a rare display of mutual amity and cooperation, they have done a fine job of beginning to address the problem.During that time, since the city finished installing a network of monitoring wells, we have seen stark evidence of how groundwater levels change constantly, throughout the city, due to localized problems that are difficult to detect and often costly to repair.