REALPOLITIK: For Mantel’s Cromwell, “The fate of peoples is made like this, two men in small rooms.” |

| Wolf Hall | By Hilary Mantel | Henry Holt | 560 pages | $27 |

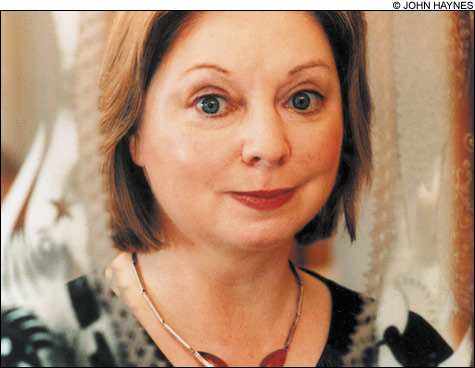

To call a 560-page novel “spare” sounds ridiculous. But though Wolf Hall is both lengthy and dense, this book — essentially a character study of the 16th-century statesman Thomas Cromwell — is also as close to bare-bones writing as one can imagine, a stark and unsentimental triumph. Largely told from Cromwell’s perceptive and at times haunted viewpoint, Hilary Mantel’s latest, the winner of this year’s Booker Prize, delves deep into a most complicated man. Extremely deep: even at this length, its six parts focus on only eight years. That this period, 1527 to 1535, changed England forever is almost incidental to Mantel’s protagonist. To Cromwell, these are simply the years of his rise, from the service of Cardinal Wolsey to that of King Henry VIII, whose marriage to Anne Boleyn he has just begun to regret as Wolf Hall draws to a close.Rooted in research, Wolf Hall depicts a Tudor England rife with realpolitik. Period detail is subtle, suggestive: Lord Rochford’s “flame-colored satin” is merely something for the vain courtier, Anne’s brother, to toy with at a time when a “pall of human ash” hangs in the air from the burning of heretics. And even in an era of so-called “new men,” Cromwell is nobody’s idea of a hero: the son of a vicious alcoholic, he enters this story as a battered boy lying in his own blood and vomit. After he flees England, we meet him again as a grown man. Along the way — and he will refer only briefly to the intervening years — he has acquired a broad education. “He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury.” He is a man of substance but also a scrapper — “like one of those square-shaped fighting dogs that low men tow about on ropes,” as Wolsey describes him, the kind of factotum great public figures need but rarely elevate to high station. But these are changing times, and Cromwell gets things — a divorce, a marriage, a Reformation — done.

Like her masterful retelling of the origins of the French Revolution, 1993’s A Place of Greater Safety, this fascinating new work shows a society in transition. A world in which major social changes come about through pragmatic, often expedient choices made in private. “The fate of peoples is made like this, two men in small rooms,” Cromwell notes. “This is how the world changes: a counter pushed across a table, a pen stroke that alters the force of a phrase.”

That the people making these decisions have been shaped by horrific pasts is unimportant to them. Not unimportant, perhaps, to the world. “There is no trace of a smile on the face of his painted self,” Cromwell realizes, seeing his own portrait, and he recalls a hurtful comment: “I looked like a murderer.” To which his son can only reply, “Did you not know?” For Cromwell, as for earlier Mantel protagonists Camille Desmoulins (A Place of Greater Safety) and Alison Hart (Beyond Black), the crucible of early trauma forges a certain toughness of spirit, a ferocity that’s reflected not only in their actions but in Mantel’s direct, concrete language.