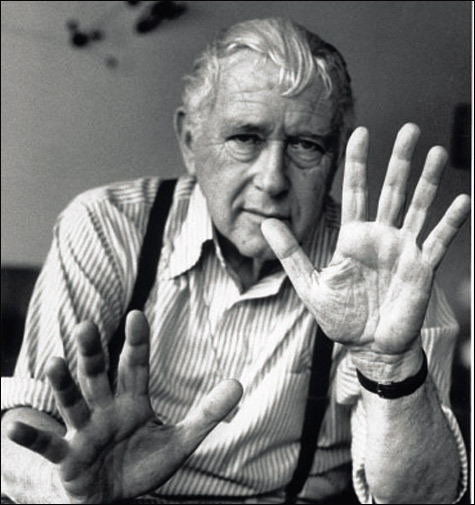

REVOLUTIONARY Breuer in 1975. |

It is one of the icons of 20th-century design. What distinguishes Marcel Breuer's B34 armchair from 1928 is its materials (fabric seats slung between steel tubing) and the lack of rear legs. The chair levitates on a continuous line of metal — from the runners, up the legs to the armrests, which in turn support a loop of tubing that forms the seat and back. It's the epitome of stripped-down elegant machine-age Modernist cool.So begins "Marcel Breuer: Design and Architecture," on view at the RISD Museum (224 Benefit Street, Providence, from April 17 to July 19). Organized by Vitra Design Museum in Germany, it marshals furniture, photos, brochures, architectural models, video, and pull-out architectural plans to beautifully, clearly, dashingly enumerate the ideas and development of one of the most influential designers of the past century. It is one of the best shows you'll see in New England this year.

Breuer was born in Hungary in 1902, became a star pupil at Germany's legendary Bauhaus design school, taught there and, as the Nazis seized power, at Harvard, before setting up shop in New York, where he died in 1981. He is credited with designing the first tubular steel chair, the "Wassily" club armchair B3, in 1925. It uses the same materials as the B34 (fabric, steel tubing) but is more elaborate. Both are like line drawings turned 3D, but the B3 could be the variation for the forward-looking but august lords of an old university club.

The B34, on the other hand, is a chair pared down to its atomic particles. It has a slight recline of the back, gradual curves, and a gauge of tubing that gives it a distinctive springiness. It stands without back legs because of its cantilevered design — a favorite device of Modernists because it shows off the strength of innovative construction materials. Breuer probably wasn't the first one to come up with this basic design, but his version, widely produced and copied, is the one people remember.

"One hears the following objections to tubular steel furniture," Breuer said in 1927. "It is cold, fit for a hospital, reminiscent of a surgical chair. These comments blossom and wither from one day to the next — they are products of habit — and soon supplanted by some other habit."

Hear the 25-year-old's determination, confidence, disdain, swagger. It's the language of a revolutionary. The Bauhaus is remembered for inspiring spare, clean, geometric, minimalist design — and endless drab glass, steel, and reinforced-concrete box buildings. But it was driven by a utopian vision. They hoped to flatten class distinctions by producing elegant but affordable mass-produced designs. They saw their geometric style as a universal language that could transcend national divisions. The masses never really embraced it, but Bauhaus style proliferated because glass, steel, and reinforced concrete buildings remain the cheapest thing going.

Breuer's continued exploration of new, affordable, industrial materials led him to devise a super-slinky chaise longue from honey-hued molded plywood in 1935. As manufactured by Isokon, the streamlined seat curves like rolling water, a belly dancer, a silk scarf in a breeze.

Arriving in the United States in 1937, Breuer turned increasingly to architecture. He favored rectangles, grids, right angles. He moved horizontally, favoring massive rectangular boxes and flat roof slabs. (He built just one skyscraper.) His structures — like the house he built for himself in Lincoln, Massachusetts, beginning in 1937 — often were a series of various sized abutting boxes.

When Breuer's furniture didn't hit the sweet spot between less is more and less is less, his designs turned awkward, uncomfortable, cold. When his architecture goes wrong it's harsh, oppressive, affected — like New York's Whitney Museum of American Art ('64-'66). The Brutalist design of boxes stacked one atop the next like an upside-down pyramid resembles a fortress.

Better are buildings begun in the late '50s, like Begrisch Hall at New York University or St. John's Abby Church in Minnesota, which channel Space Age optimism and atomic angst. The hall looks like a spaceship perched on three legs. The church features a "bell tower" consisting of a flat stone slab on four legs that resembles a Stone Age radar array. They're weirder and warmer. Like his landmark chairs, they break away from ruthless rectangularity by way of soaring curves.