FED UP: One of Portnoy’s favorite words takes on new resonance in Roth’s latest novel. |

| Indignation | By Philip Roth | Houghton Mifflin | 256 pages | $26 |

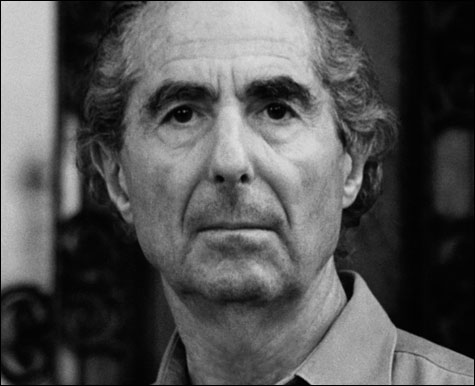

We all know Philip Roth’s preoccupations. They have, after all, been preoccupying the man for 28 books now, and there is nothing in his 29th, Indignation, that will leap out as a new concern. The great thrashings of male adolescence and the intersections of individual will and American history are the subjects of this strange and powerful little novel. The name on the cover is almost gratuitous. Like we wouldn’t know that this is Philip Roth?The hero of Roth’s knotty parable is Marcus Messner: Jewish, anxious, smart, born and raised in Newark. His mother is motherly, in a fairly bland way. (Here, as is frequently the case with Roth, it’s the men who are awarded complex personalities while the women move along the familiar paths.) His father is a kosher butcher, and Marcus grows up helping out. Marcus loves his father, loves learning how to do the unpleasant things that have to be done, and so it is acutely painful when his father suddenly becomes fearful that Marcus might die. “What is this all about, Dad?”, Marcus asks after one of his father’s irrational, overprotective outbursts. His father cries, “It’s about life, where the tiniest misstep can have tragic consequences.” Angry, fed up — heartbroken, really — Marcus heads to the well-kept Ohio campus of conservative Winesburg College. It is 1951.

At Winesburg, Marcus encounters the things one tends to encounter at college: inexplicably malicious roommates, pompous administrators, sex. It happens that, in an unexpected way that I shouldn’t spell out completely, Marcus’s father is right, that the tiniest little missteps can bloom into tragedy. Although it never fully enters into the scene until the novel’s epilogue, the Korean War hangs like a specter over Marcus, who realizes that it’s either straight A’s or the draft.

This gnawing fear gives intensity to Marcus’s fervid introspection. Roth’s long sentences take deliberate steps, homing in, ruthlessly, on their subjects. Here is Marcus seeing his mother, who is planning to divorce her anxiety-ridden husband: “Now suddenly she was herself, ready and able to do battle, and I was the one at the edge of tears, knowing that none of this would be happening had I remained at home.” There is considerable force in the little moral that closes off that sentence, and even more pathos in the sentence that follows. “It takes muscle to be a butcher, and my mother had muscles, and I felt them when she took me in her arms while I cried.”

Perhaps the novel’s strength derives from slow brewing. In Portnoy’s Complaint, the book that still makes Roth’s reputation, the eponymous protagonist brings his throbbing brain momentarily to rest on a song that his grade-school teachers identified as “The Chinese National Anthem.” Portnoy remembers every word: “And then my favorite line, commencing as it does with my favorite word in the English language: ‘In-dig-na-tion fills the hearts of all our coun-try men! A-rise! A-rise! A-RISE!’ ”