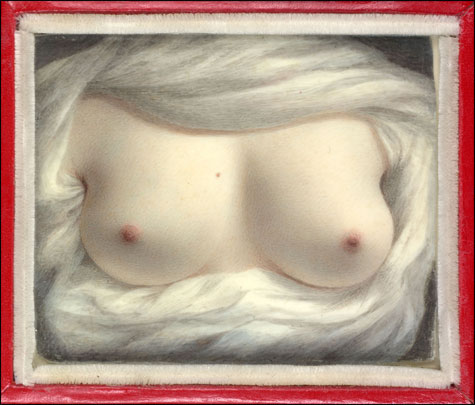

BEAUTY REVEALED: Was Sarah Goodridge’s 1828 painting a self-portrait? And a token for

Daniel Webster? |

Picture two wedding dresses. On the left is a slinky Vera Wang number from 2004. It’s a sleek, strapless couture creation in satin and silk jacquard, with white-on-white stripes that wrap around it and show off the lady’s curves. It looks like something Cat Woman would wear on her special day.On the right is a prim, pleated, hand-sewn white cotton dress that Sarah Tate wore when she got married, probably in the 1840s, maybe in Texas. It’s as plain as the Wang dress is flashy. What’s extraordinary about it is that Tate was an African-American slave. It’s a rare surviving relic from a time when slaves could not legally wed but some owners allowed them to marry informally. Wow.

What we have here in the opening gallery of “Wedded Bliss: The Marriage of Art and Ceremony” at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum is a show that stretches from va-va-voom to the solemn roots of marriage in our culture. And maybe says a bit about — if I dare be so grand — the magical, irresistible force of love.

Despite its cheesy title, “Wedded Bliss” is a dramatically displayed collection of fabulous stuff from the museum’s collection and lots of loans, and it’s given ballast by the scholarly recognition that weddings — as one of the ancient, common, and fundamental rituals of societies around the world, a celebration of the union of existing families and an elemental building block of communities — call forth some of humanity’s greatest artistry. The show is not so much about fine art as about the creativity that goes into gowns and crowns, ritual gifts, the ceremony’s pageantry. It’s rich territory because, of course, in many cultures weddings are events on which no expense is spared.

In the art world, there is much love of folk art, and lip service is paid to the Duchampian notion that anything can be art, but fine art still ranks higher than folk. The Peabody Essex’s definition of art is broad and non-hierarchical, so we get dresses and quilts, wedding trunks, and things like Cile Bellefleur Burbidge’s Architectural Fantasy Cake. Executed just for the show, Burbidge’s creation is an astonishing stepped tower of flowers and garlands and swans and a giant pot bursting with flowers on top, all made of stiff white icing mixed from eggs and sugar. Burbidge, who’s from Danvers, is a celebrated cake designer, but what other local museum would have the guts to put her piece in its show rather than unveiling it at the VIP reception?

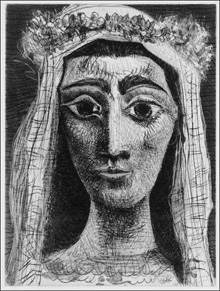

JACQUELINE DRESSED AS A BRIDE: Even

Picasso has trouble keeping up with the

treasures here. |

The exhibit was organized by Peabody Essex textiles and costumes curator Paula Bradstreet Richter, whose eye for such things is so sharp that the marquee artists here — Picasso, Chagall, Jacob Lawrence, William Hogarth, Winslow Homer, Alex Katz, Augustus Saint-Gaudens — have trouble keeping up. Or maybe she doesn’t have quite the eye for the marquee stuff, though I like Claes Oldenburg’s crisp 1966 white plaster of Paris cake slices called Wedding Souvenir. The show also makes stabs at critiquing gender politics and patriarchy, but these artworks are too blunt, too blithe, to hit home. Aren’t there some acid Barbara Krueger pieces that should be here?But marvel at wedding traditions from around the globe. Wodaabee Wedding (1999), from Italian photographers Tiziana and Gianni Baldizzone, shows men in Niger doing a ritual courting dance with their faces painted ocher, black rings around their eyes and mouths, and white stripes down their noses. To unfamiliar eyes, it feels like something from a dream. A 1762 painting shows the blasting cannons of an armada of ships as a barge ferries 17-year-old German princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz to England to meet her betrothed, King George III. Indian photographer Dayanita Singh’s recent images document extravagant Indian wedding stages that could be the sets of movie musicals. A tunic-like wedding huipil in the traditional style of the Mayan women of Chiapas is woven with elaborate brocaded patterns. A gold-colored Chinese bridal headdress from the early 20th century is decorated with turquoise dragons and orange pompons.

Then the exhibit stops you in your tracks with something like the diamond-encrusted, velvet-lined nuptial crown that Princess Alice of Hesse-Darmstadt (later Empress Alexandra) wore at her wedding to the last tsar of Russia, Emperor Nicholas II, in St. Petersburg in 1894. Forced to abdicate in 1917 by the Russian Revolution, they were executed the following year. The crown was seized by the Bolsheviks and eventually acquired by an American collector, so it makes an appearance here.