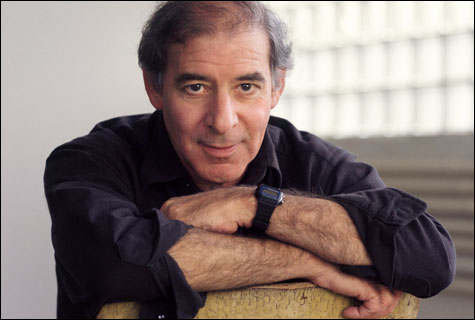

AFTER SMILEY: The complexity of Furst’s tales put him in the forefront of the latest wave of espionage writers who play on the moral ambiguities of “the good war.” |

| The Spies of Warsaw | By Alan Furst | Random House | 288 pages | $25 |

The gray afternoon, the loveless assignation, the endless bureaucracy. By any measure, the clandestine world of Alan Furst is as far from that of centenarian Ian Fleming’s as John le Carré’s. But as his evocative new The Spies of Warsaw shows, Furst’s spies — particularly his latest, the dashing Colonel Jean-François Mercier — merit a little more romance than the cold, small clerks of le Carré’s world, at least more than George Smiley ever had.Warsaw, Furst’s 10th novel in the “Night Soldiers” series, opens, like its predecessor The Foreign Correspondent, with an assignation. Edvard Uhl, a senior engineer at a Breslau foundry, has been lured into an affair. His big, brassy lover, who styles herself the Countess Sczelenska, just happens to have “friends” who would like Uhl’s help in obtaining plans for armaments manufactured at the German foundry. Unlike The Foreign Correspondent, which viewed such a meeting through the cold eyes of a waiting assassin, Uhl’s romance is experienced firsthand, doubts and all. “And was she a countess? A real Polish countess? Probably not, he thought. But so she called herself, and she was, to him, like a countess.” Self-deception is only one of many layers shielding the citizens of Eastern Europe in autumn, 1937, as the continent grinds toward war.

The sex enjoyed by Mercier is equally loveless — “a man of the world, a woman of the world, a brief, pleasant adventure, all memory courteously erased” — but the participants more honest. Mercier is a lone wolf of a hero. An aristocrat, a graduate of the prestigious Saint-Cyr military academy, Mercier serves as France’s military attaché in Warsaw, a wound from the Russo-Polish war of 1920 having necessitated his move into the diplomatic service. From here, he runs Uhl and the “countess,” and undertakes other little adventures with the help of his bluff Polish driver, Marek. Like his Saint-Cyr classmate, Charles de Gaulle, Mercier believes Germany is planning to invade. But Pétain and his cohort are in power, and all Mercier can do is file reports and wait.

This is familiar territory for Furst, and his growing legion of fans will recognize what has almost become formula: the small struggles of ordinary people as war clouds gather. The “Night Soldiers” books are only loosely connected; characters recur in some of the earlier books, and, in Warsaw, the fictional Brasserie Heininger once again serves as a meeting place when Mercier makes it to Paris. But they all share the same time frame (1934–1941) and similar urban settings: European cities under pressure, where small acts of heroism can make a difference, or cost an individual all.

For Mercier, the obstacles to action are everywhere. Still mourning his wife, dead three years, he only slowly allows himself to pursue a beautiful, and somewhat unavailable, French-Polish lawyer. And though he manages to scout out the German-Polish border, despite his bad leg, he is truly hobbled by his government’s policies, and by the mundane nature of his job.