BISHOP’S DICTUM? “repeat, repeat, repeat; revise, revise, revise.” |

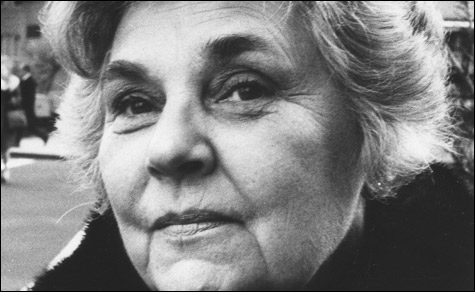

Although she has in recent years broken through to a wider readership, Elizabeth Bishop was always first and foremost a poet’s poet, a touchstone of uncompromised excellence and integrity, a fastidious maker of verbal occasions that become more resonant with each reading. In her lifetime (she died in 1979) these were gathered slowly — frugally, one might say — into thin books bearing titles like A Cold Spring, Questions of Travel, and Geography III, all of which took on the status of classics even while the ink was still damp.

Bishop aspired to absolute craft, an idea of perfection, her dictum succinctly encoded in her poem “North Haven,” which she wrote in memory of her dear friend Robert Lowell: “repeat, repeat, repeat; revise, revise, revise.” Such aspiration requires the most implacable exertion of control, and it assumes the maker as ultimate arbiter. But it was this very assumption that was called into question several years back when New Yorker poetry editor Alice Quinn published Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments. That set off a minor literary ruckus, volleys exchanged between those who saw any hitherto unseen work by Bishop as bounty and those who felt the poet’s core æsthetic intentions had been ignored. I would put myself in the second camp — such publication seems a violation of the very principle that brought us the dazzling rightness we so admire — but at this point I won’t argue further, citing instead the old adage about the horses having fled the barn or the other one about the milk having been spilt.

Maker of occasions and fashioner of thin books that Bishop was, I wonder how she would greet the publication now of the thick Library of America compendium. It’s as close as an American writer can come to being canonized — and even modest Bishop would not have repudiated that: to be modest is not to be unambitious. On the other hand, a volume like this enfolds an austere private practice into a numbingly public aura. My guess is that she would have been ambivalent about the whole business, and possibly distressed about the display of her correspondence.

But if anything could have allayed her anxieties, it would have been the knowledge that her editors were her friends Robert Giroux (who was also her editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and Lloyd Schwartz (who’s the Phoenix’s classical-music critic). The two have been scrupulous to the highest degree, fashioning a presentation that honors her greatness as a poet (with special attention paid to her careful sequencings) and at the same time reveals her range as a writer of stories, reportage, and essays, along with her gifts as a translator and a free-spoken correspondent.