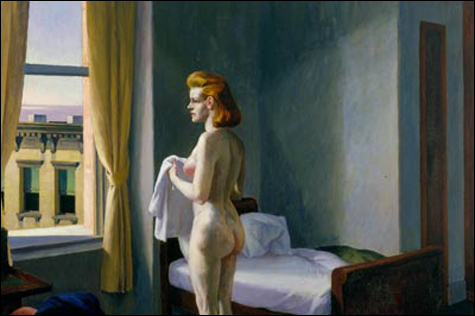

MORNING IN A CITY: Women staring out the open windows of cheap apartments and hotel rooms. |

In Edward Hopper’s world, everyone is lost in an unending rut of office overtime, rattling El trains, cheap fluorescent diners, and bad dates. Everything has fallen tensely quiet. And this anxious, itchy mood haunts even the urban landscapes — perhaps half his work — in which the only person around is you, the viewer. Here every man is an island.

“Edward Hopper,” a career-spanning survey that opens Sunday at the Museum of Fine Arts, reminds us that Hopper has become perhaps the most famous and beloved American artist of the past century by picturing the disquieting film noir isolation lurking at the glass-and-steel heart of our modern metropolises, the frustration of being alone when we’re so damn together. Organized by the MFA, the National Gallery of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago and overseen here by MFA curator Carol Troyen, the show focuses on about 100 works from 1925 to 1950, including many of his most famous paintings.

Hopper (1882–1967) studied art in New York and visited France three times during the first decade of the 20th century. He spent the next 10 years roaming the artistic wilderness, but in the early ’20s he laid out what would become his signature motifs in a series of confident black-and-white etchings: tense couples, people alone in public, ladies gazing out windows, and, as he titled one print, The Lonely House. Here you see his penchant for odd, striking angles and the dramatic light of Rembrandt’s prints.

He arrived in Gloucester in 1923 frustrated by his inability to sell his art and unhappily earning a living as a teacher and an illustrator. The introspective romantic 41-year-old hung around the fishing port and artist colony with Josephine Nivison, a gregarious New York painter a year his junior who soon became his main squeeze. She encouraged him to try painting watercolors, a medium he’d abandoned, except for illustrations, a decade before.

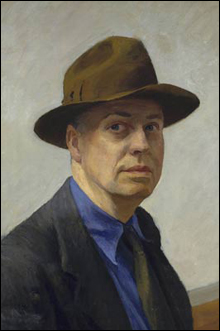

SELF-PORTRAIT: The anxiety of the aftermath of a million bad dates — in his art, but not his life. |

That summer and the next, when the couple, now married, returned to Gloucester on a sort of honeymoon, Hopper found his mature style. The Mansard Roof (1923) is a loose, animated watercolor of a big white house as a confection of awnings and windows and dormers framed by wind-ruffled trees. It reflects Hopper’s early soft-focus style, combining the dashing dark realism of his New York teacher Robert Henri and the Impressionism of Camille Pissarro and Childe Hassam. Next to this painting hangs Haskell’s House, from the following year. It depicts another white Gloucester house with a mansard roof, but Hopper has a new Yankee sobriety and austerity. It’s as if Gloucester’s crisp clear North Atlantic light had knocked the fuzzy fussy Frenchness out of him.His 1920s Gloucester watercolors will be a revelation to those who know him only from his lonely urban dramas. Coming out of the gritty realism of Ashcan School painting, Hopper frankly examines Gloucester’s tired buildings, trains, and fishing boats — sights generally considered hideous at the time. People are absent. Buildings are often dramatically cropped in a way that suggests the influence of photography. But what electrifies these scenes and fills them with nostalgia is the light. Hopper favors what filmmakers call the “magic hour,” when the sun is low in the sky at the start and the end of the day, spotlighting parts of the landscape with warm golden rays and throwing the rest into dramatic shadow.

Hopper spent his winters in a fourth-floor apartment in Greenwich Village, but he bought land on which to build a house in Truro in 1933, and he summered there most every year for the rest of his life. Although he traveled across New England, New Mexico, South Carolina, California, and Mexico looking for subjects, his focus is manmade landscapes. Paintings of roads rolling over Cape Cod’s windswept dunes and sturdy Maine lighthouses speak of taming nature.

His New York is all rusty rooftop pipes and chimneys, the girders and trusses of bridges, sickly-green electric lights. He increasingly focuses on oil painting. And people begin to appear in invented scenes that hint at mysterious stories we can’t quite puzzle out. They’re inspired by movies and plays and memories of places glimpsed during walks and train rides. His vantage point is often high, from a building or an El train, peeping into windows across the way or down to the street below. He loves doors and windows, where inside meets outside.

Women are the stars, usually in tight outfits or scantily clad, energizing canvases with their sexuality, their vulnerability, their unattainableness. Like the woman in the 1944 Morning in City, they appear alone, exhausted and sad, hardened by life, staring out the open windows of cheap apartments and hotel rooms. He spies couples alienated from each other in claustrophobic Manhattan apartments. In Automat (1927), a woman sits by herself at a restaurant table at night, nursing a cup of coffee or tea. In New York Movie (1939), a bored usherette leans against a wall of a grand, velvety movie palace. To the left, a man and a woman sit alone together in the darkness, escaping into a Hollywood fantasy.