THE RICH SOIL DOWN THERE: The fantasia of race and sex and shit manifests themes of power and slavery. |

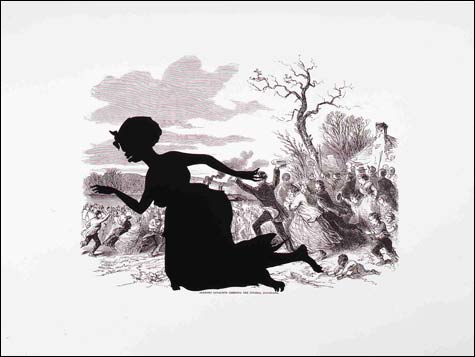

In February 1862, with the Civil War not yet a year old, Union forces took Fort Henry, a Confederate outpost on the Tennessee River, as they began to open up Southern waterways for supply lines. They then continued down along the river through Confederate Tennessee and into Alabama. “We have met the most gratifying proofs of loyalty,” a Union lieutenant reported. “Men, women, and children, several times gathered in crowds of hundreds, shouted their welcome, and hailed their national flag with an enthusiasm there was no mistaking.”An illustration published in the two-volume Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War of 1866 and 1868 documents just such a scene. In 2005, New York artist Kara Walker revised the original by adding the black silhouette of an African-American woman who has tripped at the back of the white throng rushing down to the river. She wears a ragged skirt and a kerchief is tied around her hair mammy-style, but she’s topless. Her presence calls attention to a fully clothed black woman (a wet-nurse slave?) who’s at the back of the crowd in the original, dashing along cradling a white baby in her arms. A little black boy stumbles to the ground behind her, in danger of being left behind and maybe trampled.

It’s one of the prints from Walker’s 2005 series “Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated),” which is on view at the Philips Academy’s Addison Gallery through April 15. Walker enlarges lithographs of the Harper’s originals and screenprints her signature black silhouetted characters on top, as if they were graffiti moustaches elegantly scrawled on billboards. The silhouettes become ghosts (a reference to the slur “spook”?) haunting the Civil War, interrogating the portrayal of African-Americans in history and their role in the war.

ALABAMA LOYALISTS GREETING THE FEDERAL GUN-BOATS: Walker makes you realize how easily classifications of race and gender can slide into bigoted caricature. |

Walker, who’s now 37, lived in California until her family moved to Atlanta when she was 12. “When I was coming along in Georgia, I became black in more senses than just the kind of multicultural acceptance that I grew up with in California,” she said in a 1999 interview with New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “Blackness became a very loaded subject, a very loaded thing to be — all about forbidden passions and desires, and all about a history that’s still living, very present . . . the shame of the South and the shame of the South’s past; its legacy and its contemporary troubles.”While studying at Rhode Island School of Design, where she earned a master’s degree in 1994, she made her great formal move: reviving the 19th-century art of the cut-paper silhouette. It had been seen as decorative and a women’s medium and had long been out of favor except in second-grade classrooms — three strikes against it in the art world. Walker seized on it for these very reasons: it was beautiful, it spoke of womanhood, it spoke to history. And the stark black paper stuck to white walls was an elemental metaphor for race.

The Museum of Fine Arts has her The Rich Soil Down There, a stenciled paint version in black and white on gray of a 2002 cut-paper mural, hanging in the Upper Galleria of its West Wing. The scene is an ante-bellum plantation. A pants-less black boy carries a refined white lady atop his head. Her legs are fantastically splayed as she squeezes out a puff of white shit. (Walker seems to represent excrement with a variety of rounded or drippy shapes.) A black man and woman are covered by white goop. A white Sambo, with a flower stuck up his ass (looks like a Devil’s tail), reaches his hand under the framing of a hoop skirt of a busty girl dancing with flowers in her hands. A black girl strokes an aristocratic white boy’s saber cock to orgasm. Cartoon crows, like those in Dumbo, flap above, shitting.

It’s a filthy fantasia of race and sex and shit, where every bodily urge is expressed at its most animal. And it’s told through Walker’s wicked repertory company of stereotypes: mammies and pickaninnies, Sambo and Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, Neanderthal slave bosses, and the Southern belles and house slaves of Gone with the Wind. It’s electrified by sex — Walker’s most telling and controversial character is a slave vixen who’s forever trying to seduce and manipulate the “good” and “just” white folks. And it’s ultimately about the workings of power, particularly as manifested in racial and sexual relations — and slavery, their utmost intersection.

This is the terrific and unnerving stuff that has shot Walker to the heights of the art world during the past decade, with shows at the Whitney Biennial, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A major retrospective opens at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center on February 17.